Presentations succeed when an audience receives, interprets, and retains ideas with minimal distortion. Communication models are practical frameworks that explain how meaning travels between people and why it sometimes breaks down. For presenters, these models translate into design and delivery choices: how to sequence arguments, how to balance speech and visuals, where to place interaction, and how to protect clarity in rooms with competing stimuli. Treat them as operating manuals for live communication rather than abstract diagrams.

In a presentation setting, constraints are explicit. The clock is visible. Attention fluctuates. Slides compete with the speaker’s voice, room conditions, and devices in pockets. Models help you decide what deserves emphasis at each minute mark and how to encode messages so audiences can decode them quickly. They also reveal where interference appears: vague wording, crowded slides, confusing metaphors, mismatched tone, or a lack of feedback. The most useful outcome of thinking in models is not a prettier diagram; it is a more reliable talk that moves from intention to measurable effect.

In this article, we will explore the different models of communication applied to presentation design and delivery, and how to select one of these approaches for your topic and style.

Table of Contents

- What is a Communication Model?

- How to Choose a Communication Model for Your Topic or Style

- Aristotle’s Communication Model: Structuring Persuasion

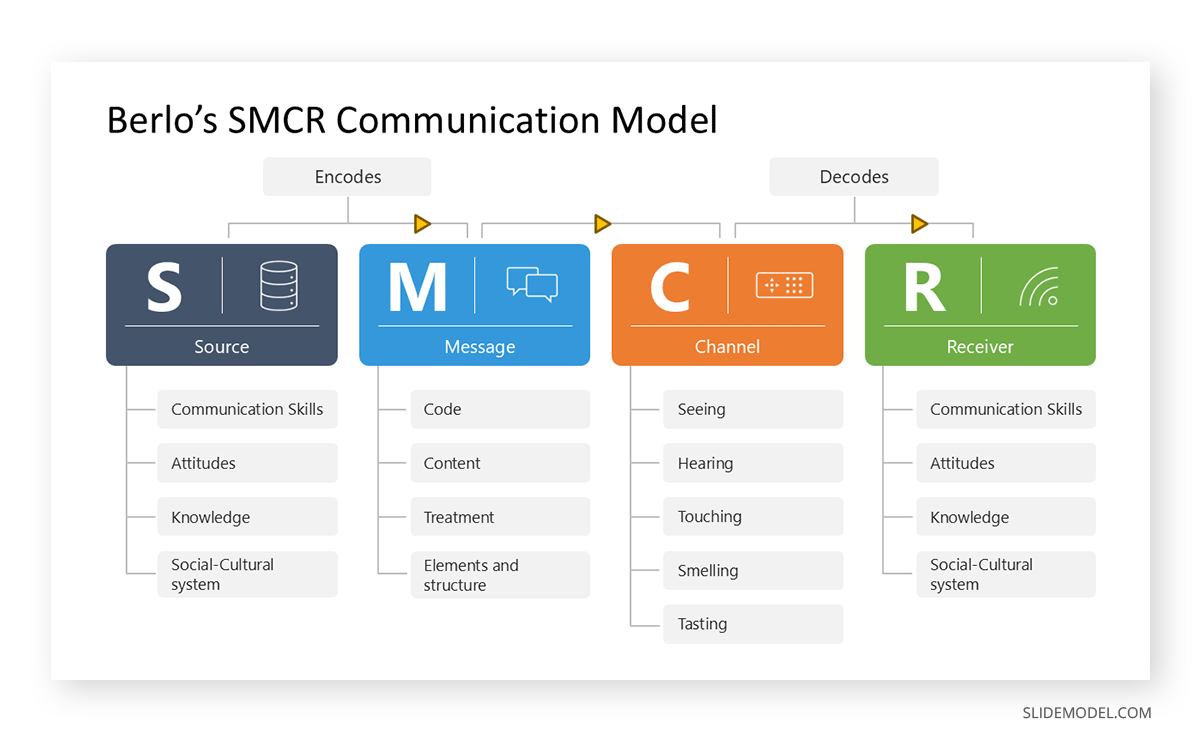

- Berlo’s SMCR Model: Encoding for the Audience You Have

- Lasswell’s Model: Design Backward from the Effect

- Shannon and Weaver: Engineer Clarity and Resist Noise

- Osgood-Schramm: Build Continuous Feedback into the Room

- Westley and MacLean: Design for Mediation and After-Circulation

- Barnlund’s Transactional Model: Orchestrate Multichannel Meaning

- Dance’s Helical Model: Build Knowledge in Expanding Loops

- FAQs

- Final Words

What is a Communication Model?

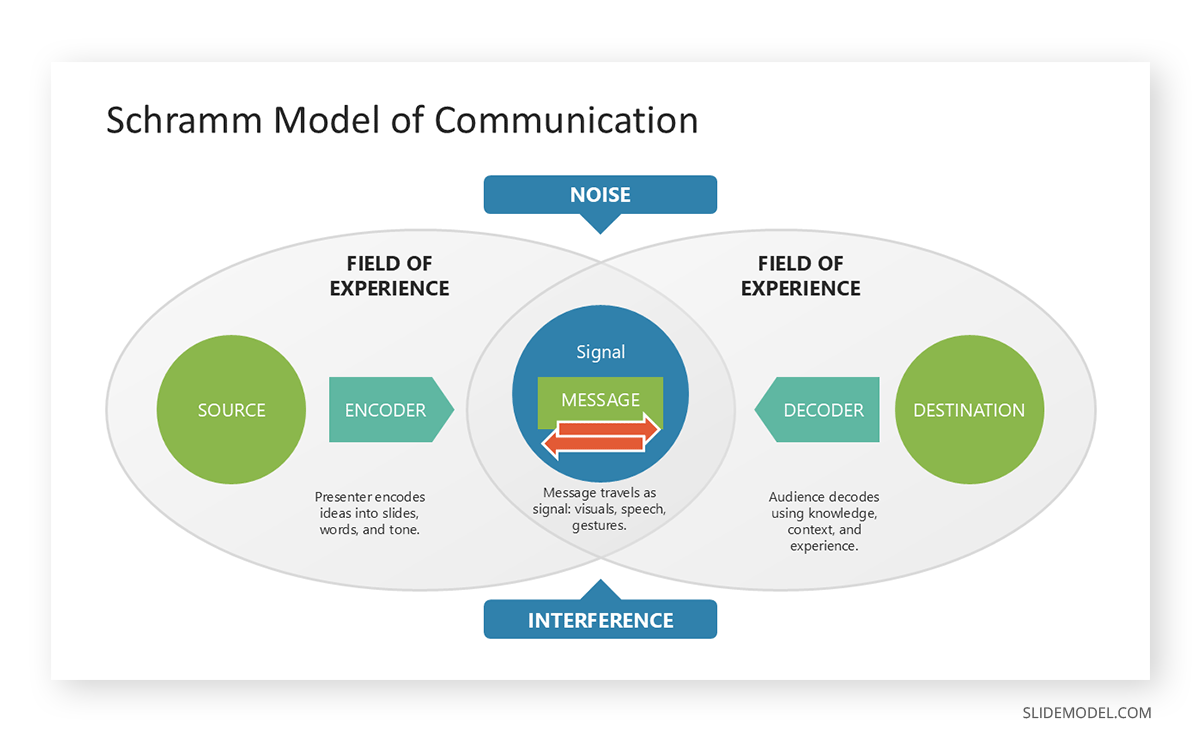

An information communication model is a structured explanation of how a message is created, encoded, transmitted, decoded, and interpreted by individuals situated within a specific context. In practice, it tells a presenter who is involved, which channels carry the message, which forms of interference to expect, and where to insert feedback loops. Instead of memorizing vocabulary, use models as planning scaffolds. They help you answer design questions before you open your slide software: what the audience already knows, what they care about, what proof they will trust, and how the environment might distort your signal.

For slide design, models clarify encoding. Encoding encompasses choices such as font size, color contrast, chart type, data labeling, and the balance of text to visuals. If the audience decodes your slide faster than you speak, the room feels in control, and engagement rises. If decoding lags, because of small fonts, stacked bullets, or jargon, the talk slows while confusion grows. A model also forces you to plan redundancy. Spoken narration can carry nuance while a diagram carries structure; notes or handouts can carry detail for later. This layered approach prevents a single point of failure.

In presentation delivery, models govern pacing and feedback. They encourage early audience calibration: quick questions, a show of hands, or a simple scenario to verify assumptions about expertise and expectations. They also prompt contingency planning. When a venue introduces noise (poor projector brightness, unstable Wi-Fi, limited audio), the model reminds you to route around the problem: adjust slides to higher contrast, narrate a demo instead of streaming it, or switch to an offline clip. Think of models as decision aids that guard clarity when conditions are imperfect, which they often are.

How to Choose a Communication Model for Your Topic or Style

Selection starts with purpose. If your goal is to persuade a board to approve funding (i.e., a board presentation), use a model that centers on argument and credibility. If your aim is knowledge transfer in a training workshop, choose a model that emphasizes audience skills and decoding. If success depends on interaction, pick a model that puts feedback at the center. From there, match channel and constraints: in-person versus virtual, time available, expected distribution of the deck after the event, and the likelihood that others will retell your message. The right model aligns with these realities rather than fighting them.

Map topic complexity to audience familiarity. When the gap is large, you need a model that foregrounds encoding decisions and supports stepwise build-up. That leads toward Berlo’s SMCR and Dance’s Helical model. When the outcome must be observable, such as sign-off, purchase, or policy change, Lasswell’s formula shines because it forces you to define “with what effect” before touching a slide. If the environment will inject interference (difficult acoustics, hybrid rooms, heavy terminology), Shannon and Weaver will help you design for resilience by stripping noise and adding redundancy.

Finally, respect interaction norms. Town halls, workshops, and design reviews benefit from Osgood-Schramm and Barnlund because they assume simultaneous sending and receiving. Executive briefings and press sessions often behave like mediated communication; Westley and MacLean predict how gatekeepers and later circulation alter meaning, so you design slides that can survive retelling. Try this workflow: name the purpose in a single sentence; pick the model that best predicts the risks; derive slide and delivery rules from that model; rehearse against the predicted failure points.

Aristotle’s Communication Model: Structuring Persuasion

Aristotle’s view centers on the speaker, the speech, and the audience. Persuasion arises when the audience judges the speaker credible, understands the reasoning, and feels the relevance. This is not a theatrical flourish; it is a disciplined alignment between claim, proof, and audience values. In a presentation, that alignment is visible in what you open with, which evidence you choose, and how you close the loop with a clear ask.

Design choices should signal credibility and coherence. Use consistent typography and color to create a professional baseline that does not distract from arguments. Reserve visual emphasis for the spine of your case: problem, stakes, proposed approach, evidence, and implications. Replace dense bullet stacks with structures that reveal reasoning: flow diagrams, annotated charts, and short pull-quotes tied to data. When citing research or metrics, place sources on the slide to support trust without breaking the flow. A simple rule is to make one claim per slide and defend it with one primary exhibit, allowing the narration to carry nuance.

Recommended lecture: Best Fonts for Presentations

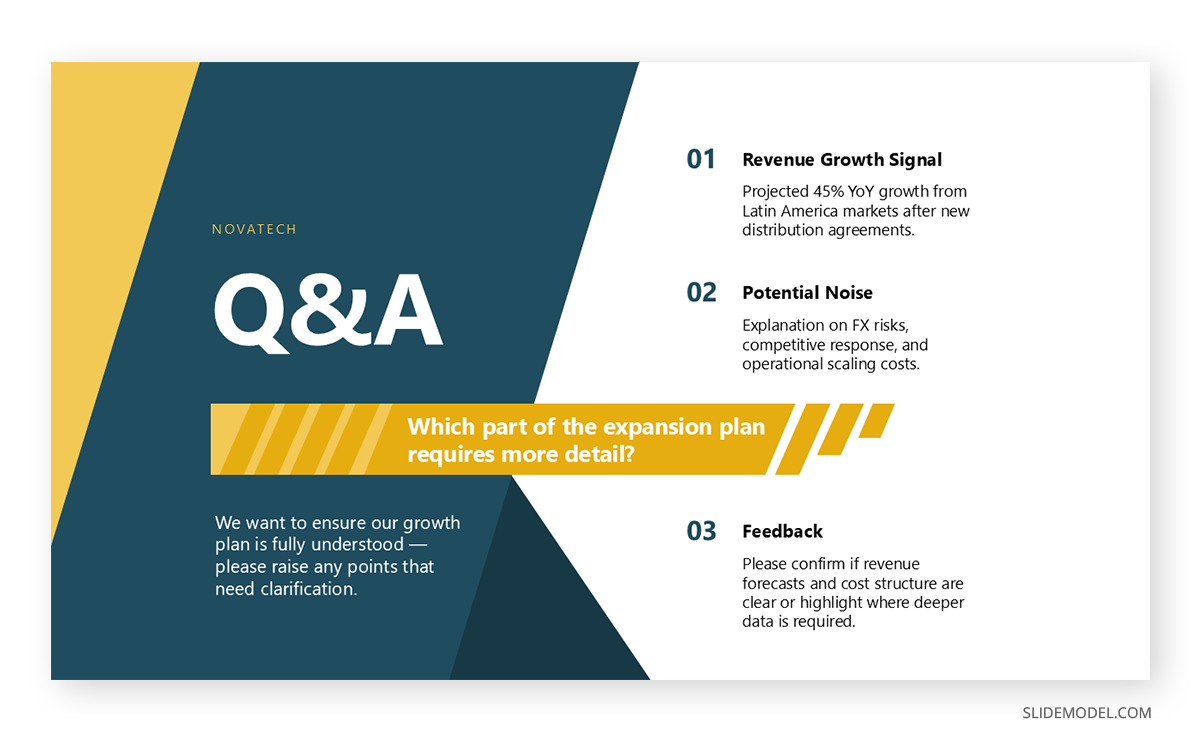

Open by clarifying the audience’s interest and the decision in front of them. Narrate evidence in a measured sequence: state the claim, show the exhibit, interpret the numbers, and link the implication to the audience’s context. Questions that surface early objections help you adjust before the close. End the presentation with a concrete request and a short recap that mirrors the structure of your slides, so the final memory matches the argument’s order.

Best-fit scenarios and risks

Aristotle’s model suits investor pitches, policy proposals, and sales presentations where judgment relies on credibility and reasoning. Risks include overloading slides with emotional imagery or relying on authority without adequate proof. Keep balance by letting visuals support the logic instead of trying to replace it.

Berlo’s SMCR Model: Encoding for the Audience You Have

The Berlo’s Source-Message-Channel-Receiver framework focuses on the competencies, knowledge, and attitudes of both sender and receiver. The model reminds presenters that comprehension depends on shared codes. If the vocabulary, symbols, or examples in your slide deck do not match the audience’s repertoire, decoding falters even when your content is accurate.

Calibrate the audience’s knowledge before the layout. Replace insider shorthand with terms your audience already uses. Choose chart forms that match their analytical habits: a simple bar chart often beats a novel visualization when time is short. Increase type size and spacing to reduce the mental effort required to read while listening. Sequence slides so each introduces only one new idea, building from familiar to unfamiliar. Where domain terms are unavoidable, add small, on-slide definitions near the first use rather than a separate glossary that forces memory jumps.

Begin with a quick diagnostic: a scenario, a short poll, or a show of hands to gauge baseline knowledge. Adjust pace as you sense friction. When you encounter blank faces, re-encode the idea verbally and visually: a new example, a simpler number scale, or a whiteboard sketch. Provide alternate channels for later decoding, such as a one-page summary or a short explainer video link, so people with different processing styles can revisit the core message.

Recommended lecture: The Feynman Technique

Best-fit scenarios and risks

Berlo’s model serves when designing training sessions, technical briefings, and cross-functional updates. The common failure mode is assuming your audience shares your guidelines. Design redundancies, captions, labels, and explicit transitions, so decoding does not depend on guesswork.

Lasswell’s Model: Design Backward from the Effect

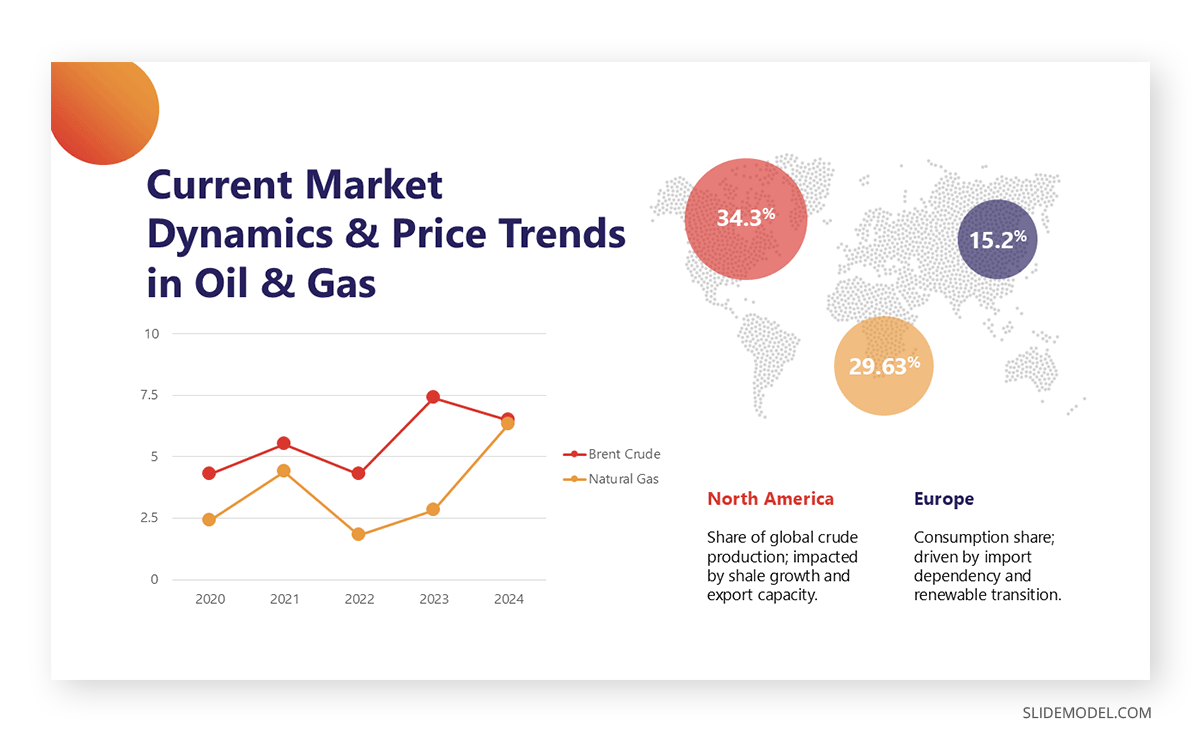

Lasswell compresses strategy into one sentence: Who says what, in which channel, to whom, with what effect: the final clause disciplines presenters. If the intended effect is decision, your slides must surface trade-offs and next steps. If the effect is awareness, your slides should package memorable frames rather than operational details. This model keeps a team honest about purpose when discussions drift toward aesthetics.

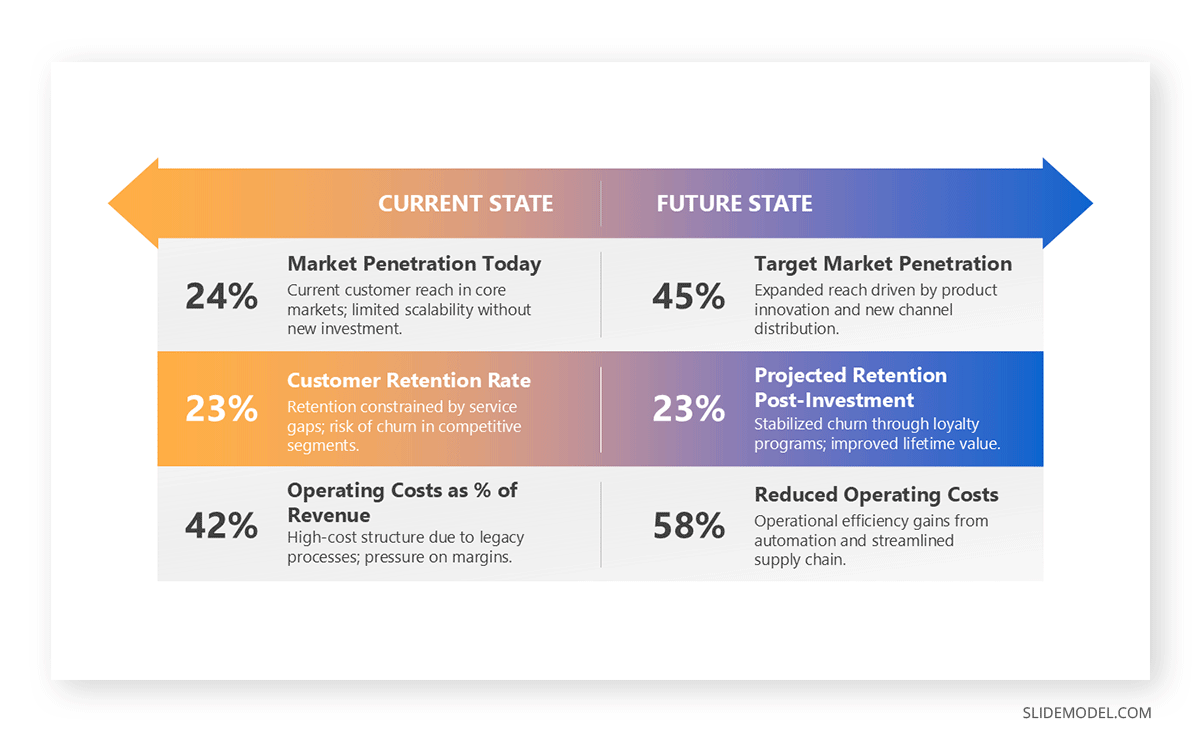

Write the effect at the top of your outline and test every slide against it. For decision effects, include side-by-side options (i.e., comparison charts), criteria, and a clear recommendation. For behavior change, include triggers, timelines, and ownership. Limit decorative elements that do not contribute to the effect; visual hierarchy should mirror the path you want viewers to follow. End sections with micro-summaries that make the intended impact explicit, so latecomers can rejoin the argument without derailing the room.

State the desired effect in your opening minute. Use the channel’s strengths: in-person affords richer nonverbal signaling; virtual demands more frequent recap and higher contrast slides. Check for commitment during the close by asking for explicit agreements or following milestones. Capture objections as inputs to a follow-up artifact rather than letting them dissolve into the air.

Recommended lecture: Visual Communication in Presentations

Best-fit scenarios and risks

Lasswell fits executive reviews, marketing plan presentations, and consultancy meetings where outcomes matter. The risk is mistaking motion for effect: busy timelines that never lead to a decision. Keep the model visible in your notes to prevent drift.

Shannon and Weaver: Engineer Clarity and Resist Noise

Initially developed for signal transmission, this model highlights encoding, channel capacity, and noise. In rooms, noise is literal and cognitive: poor acoustics, dim projectors, dense slides, jargon, or side conversations. The model asks you to increase the signal-to-noise ratio so decoding becomes effortless.

Design for legibility at the back row. Use large type, high contrast, and clean layouts. Prefer simple data displays with clear labels to reduce inferential work. Remove visual clutter that competes with the main signal. Build redundancy: say it, show it, and summarize it in a caption so a single failure does not doom comprehension. If the talk includes a demo, capture a short offline clip as a fallback and include a still image with a caption that explains the key step.

Recommended lecture: Accessibility in Presentations

Audit the venue. Check the projector brightness, microphone quality, and sightlines in the room. In virtual settings, share slides rather than screens with tiny UI elements, and narrate cursor movements. Pace so viewers can read and listen without having to choose between them. When noise intrudes: a dropped connection, a loud hallway. Pause, restate the last key idea, and resume from a visible anchor slide so the thread remains intact.

Best-fit scenarios and risks

This model is suitable for technical talks, academic presentations (i.e., thesis defense presentations), and hybrid events. The main risk is over-simplifying the message to chase clarity. Preserve nuance by keeping detail in backup slides and handouts while the live channel carries the essential signal.

Osgood-Schramm: Build Continuous Feedback into the Room

Osgood and Schramm view communication as a circular process in which participants alternate roles as encoder, interpreter, and decoder. Meaning evolves through feedback. In presentations, this means designing for continual audience signals rather than waiting until the final Q&A session.

When it comes to slide design, create moments that invite response: decision points, brief prompts, or live examples that ask the audience to apply a concept on the spot. Keep slides slightly under-specified so conversation can complete them: empty labels on a framework, a partially filled table, or a scenario that begs for inputs. Display results immediately so the audience sees their contributions alter the content, which reinforces ownership and recall.

Watch eyes, posture, and note-taking as real-time indicators. Ask short, concrete questions that check interpretation before moving to the next idea. Reflect answers into the slide narrative so contributors hear their language on screen. If a thread becomes valuable, follow it; the model legitimizes deviation when it advances understanding.

Best-fit scenarios and risks

Workshop presentations, design crits, and classroom teaching benefit most. Risks include losing structure in open discussion. Protect flow with clear checkpoints and visible section titles that make it easy to return to the planned path.

Westley and MacLean: Design for Mediation and After-Circulation

Westley and MacLean show how messages are shaped by mediators, editors, managers, journalists, and platforms, before reaching end receivers. In many organizations, your deck will be forwarded, excerpted, or re-explained by people who were not in the room. The model advises designing artifacts that survive retelling.

Ensure each key slide can stand alone. Place short context lines on the slide, add source attributions, and label axes and units directly on charts. Use consistent frames, problem, evidence, and implications, so screenshots remain interpretable when detached from narration. Provide a concise appendix with definitions and a one-page summary that captures your main claims and the action you seek.

Name likely mediators and address them in the room. Offer an export-ready PDF immediately after the talk. Anticipate misinterpretations and include clarifying notes on sensitive slides. When briefing press or cross-functional stakeholders, rehearse the two-minute version they will pass along and equip them with phrasing you can live with.

Best-fit scenarios and risks

Corporate presentations, stakeholder mapping, and press events map well to this model. The risk is flattening nuance in pursuit of portability. Counter by pairing durable slides with a live narrative that explores limits and assumptions.

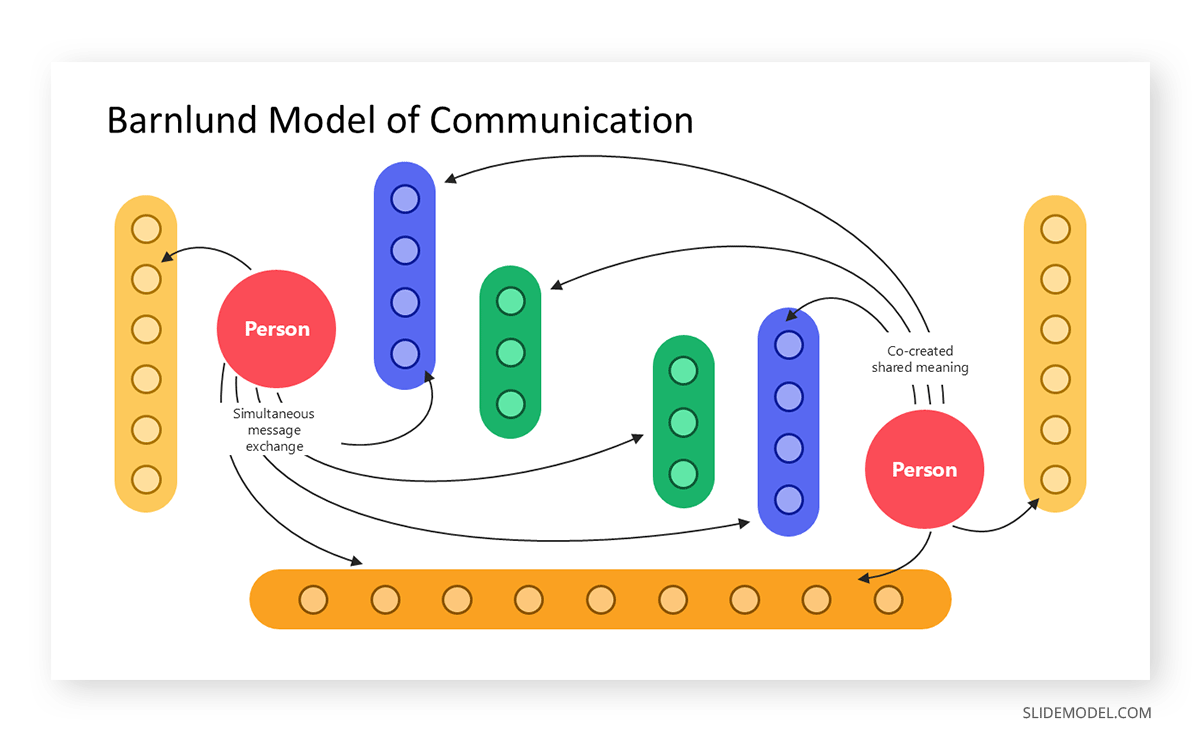

Barnlund’s Transactional Model: Orchestrate Multichannel Meaning

The Barnlund model emphasizes that communicators send and receive simultaneously through multiple channels, verbal content, tone, facial expression, gesture, and environmental cues, while context and noise shape interpretation. In a live talk, the audience reads slides and the speaker at the same time. Meaning emerges from this total field.

Let slides and speech share the workload. Keep on-screen text minimal while the narration carries the details. Use imagery with clear denotation that supports the line you are speaking at that moment. Align visual rhythm with vocal rhythm: reveal elements as you explain them, and avoid auto-advancing animations that compete with your timing. Stage the environment, lighting, movement, and placement to reduce conflicting signals.

Adopt an intentional stance: maintain stable eye contact, use deliberate pauses, and move purposefully. Monitor the room’s energy and adjust tempo. Acknowledge contextual factors (a late start, a packed agenda) so the audience has the same frame you do. When tension rises, slow the cadence, surface assumptions, and restate shared goals before proceeding.

Best-fit scenarios and risks

Negotiations, leadership presentations, and sensitive change communications benefit most. The risk lies in uncoordinated channels: busy slides, rapid speech, and restless movement that fracture attention. Rehearse with video to align channels before the event.

Dance’s Helical Model: Build Knowledge in Expanding Loops

Finally, Dance depicts communication as a helix that grows with each turn, integrating past experiences into future meaning. For presenters, this is a plan for progressive complexity: start from the audience’s prior knowledge, introduce a new layer, and circle back with reinforced connections so the next layer lands faster.

Structure your deck in visible loops. Begin with a familiar anchor: baseline metrics, current workflow, or a known pain point. Add one variable, show its effect, and connect it to the anchor with a short recap statement on the slide. Use consistent visual motifs so each loop feels related to the last. Revisit the opening slide near the end with updated annotations to make the growth in understanding tangible.

Signal each turn of the helix with verbal markers: “Returning to our baseline, here is what changes after step two.” Encourage recall by asking someone to summarize the previous loop before you add the next. Close by mapping all loops on one synthesis slide that shows the full path from the starting point to the final recommendation.

Best-fit scenarios and risks

Multi-session training, complex change programs, and academic lectures align well. Risks include spending too long on early loops and running out of time for synthesis. Guard time boxes and keep each turn focused on a single added dimension.

FAQs

Why should presenters care about communication models?

They act as planning tools. Instead of guessing how to build a deck, models highlight where breakdowns occur, such as unclear slides, jargon, or a lack of feedback, and suggest remedies to improve clarity and engagement.

What risks come with relying too much on Aristotle’s model?

You might overload slides with emotional imagery or lean too heavily on authority without data. Balance ethos, pathos, and logos so that persuasion remains grounded in evidence.

What does Berlo’s SMCR model teach presenters?

It highlights encoding and decoding. Presenters must adapt slides to the audience’s knowledge and skills, avoiding insider jargon and using visuals and examples aligned with audience familiarity.

How does Lasswell’s model shape presentations?

It forces presenters to design backward from the desired effect. Slides should be tested against outcomes: decision, awareness, or behavior change. It prevents design drift and keeps the purpose clear.

What’s the main risk of using Lasswell’s model?

Confusing activity with effect. Presenters may build busy decks with timelines and charts without clarifying the actual decision or outcome expected.

How does Shannon and Weaver’s model help in slide design?

It addresses noise. Presenters should strip clutter, boost legibility with high contrast, and add redundancy (say it, show it, caption it). This ensures the signal survives distractions and technical issues.

What’s the core idea of the Osgood-Schramm model for presenters?

Communication is circular, not one-way. Speakers should design interactive presentation elements, such as polls, prompts, or scenarios, that invite audience feedback during the session.

How does Westley and MacLean’s model affect slide design?

It reminds presenters that decks are often shared beyond the room. Slides must be self-explanatory, with context lines, source attributions, and clear labels so they survive retelling without narration.

What problems can occur with Barnlund’s model?

If slides are busy, the speech is too fast, and body language is restless, channels conflict. Rehearsal with video feedback helps align them.

How does Dance’s Helical model apply to presentations?

It treats communication as progressive loops, where each new layer builds on prior knowledge. Presenters should design decks in loops, start simple, add complexity, and recap before layering further.

Final Words

Models are valuable because they prevent avoidable failure. They suggest which part of your presentation to design first and where to invest rehearsal time. Before your next talk, write down your purpose, audience state, channel constraints, and the chief risks. Select the model that best matches those facts.

Build slides that express the model’s rules: one claim per slide for persuasion, redundancy for noisy environments, standalone frames for mediated circulation, explicit feedback moments for interactive rooms, or visible loops for progressive learning. Then rehearse against the specific breakdowns the model predicts.