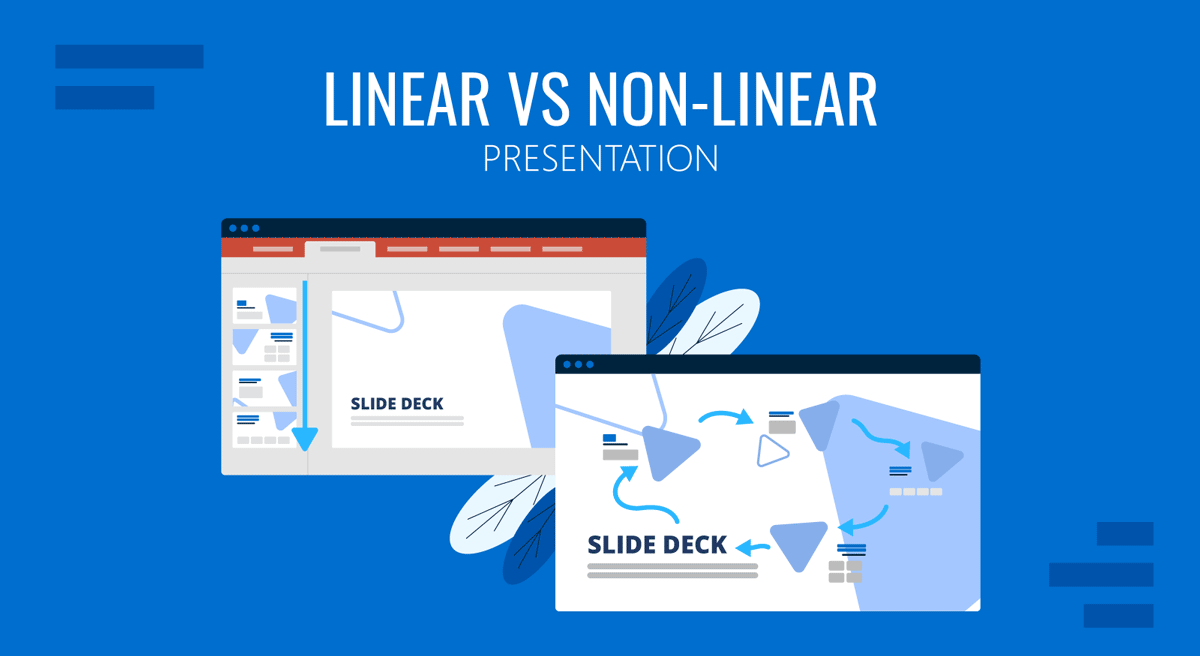

Every presentation follows a structure, whether the speaker realizes it or not. The sequence in which ideas appear determines how an audience absorbs information and how effectively a presenter maintains attention. While most presentations follow a linear progression, moving from start to finish in a fixed order, a growing number of communicators use non-linear formats to adapt in real time, answer questions dynamically, and personalize their message to the audience’s needs. Understanding both approaches is essential for anyone who aims to present complex ideas with precision and control.

Linear and non-linear presentations are not opposites; they are tools that serve different goals. A linear presentation provides a clear, predictable path. A non-linear one gives flexibility and responsiveness. Knowing when to apply each method depends on the presenter’s context, message, and level of mastery. This article examines both models in depth, focusing on their structures, cognitive flows, and performance management.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Linear and Non-Linear Presentation Structures

- The Logic Behind Linear Flow in Presentations

- When to Use Non-Linear Presentation Design

- Technical and Cognitive Aspects of Navigation

- Designing Slides for Each Structure

- Tools and Software Features Supporting Non-Linear Navigation

- Common Mistakes

- FAQs

- Final Words

Understanding Linear and Non-Linear Presentation Structures

The Nature of Linear Communication

A linear presentation follows a fixed narrative sequence. Slides progress from introduction to conclusion in a predetermined order, much like reading a book or watching a film. Each idea builds upon the previous one, creating cumulative understanding. This structure is ideal for arguments that depend on chronological development, such as project proposals, training materials, or research results. The speaker serves as a guide, setting the pace and leading the audience step by step toward a defined conclusion.

The linear approach mirrors traditional educational logic. It assumes that comprehension increases gradually and that skipping steps may lead to confusion. Because of its order and predictability, it helps audiences retain information through progressive reinforcement. The speaker benefits from clear transitions and predictable time management, while the audience experiences stability and direction.

What Defines a Non-Linear Presentation

A non-linear presentation breaks away from this single-path model. Instead of moving slide by slide, it allows the presenter to navigate sections freely. The flow can change according to audience questions, available time, or contextual relevance. Each segment functions independently, like chapters that can be accessed in any order. In practice, it may involve using hyperlinks, menu-based slides, or interactive presentation elements to navigate between topics. Yet, its essence lies not in the software technique but in the mindset: non-linearity treats information as modular and adaptive rather than sequential.

Non-linear structures are effective when audiences have diverse backgrounds or when content needs to respond to real-time feedback. For example, a consultant might use a non-linear deck to adjust emphasis depending on the client’s priorities. This model favors conversation over lecture and adaptability over strict control.

The Logic Behind Linear Flow in Presentations

Building Narrative Momentum

A linear structure excels when the message relies on narrative continuity. Stories, data explanations, and technical demonstrations benefit from a sense of momentum. By arranging ideas in sequence, presenters can create anticipation and resolution. The audience is guided from problem to solution, from cause to effect. This predictability supports cognitive processing by reducing decision fatigue: the viewer doesn’t need to wonder what comes next.

Cognitive Comfort and Attention Retention

From a psychological standpoint, linear flow aligns with how working memory operates. People absorb information more easily when it arrives in manageable, logically ordered segments. Repetition and progression reinforce memory encoding. This is why lecturers, trainers, and researchers often prefer linear formats: they allow precise pacing, planned reinforcement, and control over message hierarchy. The presentation structure ensures that each segment provides the background necessary for the next, avoiding cognitive overload.

Presenter Control and Timing

A linear organization also supports strong time management. When each section has a designated duration, the presenter can estimate the total delivery length with accuracy. This predictability helps during conferences or investor meetings where timing is constrained. It also minimizes the risk of deviating from the key narrative path. For less experienced speakers, linear presentation slides provide psychological security: the next point is always ready, and transitions require minimal improvisation.

However, this order comes at the cost of adaptability. Once a linear story begins, skipping ahead or revisiting earlier topics can break the rhythm and confuse the audience. The strength of linearity, its coherence, can become a limitation when flexibility is needed.

When to Use Non-Linear Presentation Design

Adapting to Real-Time Interaction

Non-linear design serves presenters who must respond to dynamic environments. Client meetings, product demos, classroom discussions, or Q&A-driven sessions often require shifting focus instantly. A well-built non-linear presentation functions like an interactive map: the presenter navigates based on cues from the audience. This adaptability enhances engagement because attendees feel their interests are shaping the direction of the talk.

Managing Variable Depth

Some topics require multiple levels of depth. A non-linear format lets the speaker dive deeper into a subtopic when needed or skip technical sections when the audience already understands the basics. This capability reduces redundancy and improves communication efficiency. For instance, a consultant can choose whether to open financial details or stay at the strategic overview level without leaving the main interface.

Audience Autonomy and Perception

When used skillfully, non-linear flow creates a perception of mastery. The presenter appears fluent, capable of navigating complex material effortlessly. Yet, this style demands strong structural awareness. The speaker must know precisely where each section connects and maintain narrative coherence even when sequence changes. Poorly executed non-linearity can appear disorganized or improvisational. The key is to sustain thematic unity while adjusting order.

Technical and Cognitive Aspects of Navigation

Spatial Thinking and Memory

Non-linear navigation depends on spatial cognition. Presenters must visualize the presentation as a map rather than a chain. This requires mental indexing, knowing where each topic is located and how to access it instantly. Skilled presenters often memorize anchor points, such as main menus or hub slides, that let them jump to any section smoothly. Without this internal map, navigation errors can disrupt flow.

On this basis, breadcrumbs in presentations help to bridge that gap, allowing speakers to have visual cues of where they stand.

Cognitive Load and Decision Control

Switching paths mid-presentation introduces new cognitive demands for both the speaker and the audience. Each transition requires reorientation: listeners need context to understand why the discussion moved. If these shifts are frequent or poorly framed, comprehension suffers. Therefore, non-linear flow demands careful signaling. Verbal cues such as “Let’s look deeper into this section” or “I’ll return to the previous topic later” help maintain mental alignment.

Linear navigation, by contrast, reduces cognitive effort because direction is predictable. The trade-off lies between flexibility and mental simplicity. Audiences new to a topic benefit from linearity, while expert audiences may prefer non-linear exploration where they can steer the focus. It’s not a matter of linear vs non-linear presentation; it’s how the format helps to reduce cognitive load in content-heavy presentations.

Technical Reliability

A practical aspect often overlooked is technical risk. Non-linear presentation examples rely on internal links or navigation tools. Malfunctioning hyperlinks or mis-clicked menus can break rhythm. Presenters must test these interactions thoroughly and always prepare a backup linear version in case of technical failure. For purely verbal delivery or printed materials, non-linearity loses most of its functionality; thus, context determines viability.

Designing Slides for Each Structure

Visual Coherence in Linear Decks

In a linear deck, design consistency reinforces narrative flow. Each slide should logically continue the previous one. Visual hierarchy: titles, color accents, and progressive diagrams guide attention forward. Since the presenter cannot skip randomly, every slide transition should add value.

Overly repetitive visuals reduce engagement, while abrupt design shifts break continuity. Consistent slide numbering and progression cues (such as step indicators) help audiences track their position in the storyline.

Modular Composition in Non-Linear Decks

Non-linear slides must stand independently while remaining visually unified. Each section should make sense when accessed directly, without relying heavily on previous slides. This modular design encourages autonomy and helps prevent confusion when sequence changes. The first slide of each section often functions as a reorientation point, briefly summarizing where the audience is within the broader framework.

Navigation cues, such as dropdown menus, PowerPoint icons, and visible section labels, form the backbone of the system. The design must remain minimal and intuitive, ensuring that control transitions are invisible to the audience. When visual design feels seamless, the focus stays on content rather than mechanics.

Balancing Aesthetics and Usability

Both linear and non-linear decks demand restraint. Visual effects or excessive transitions can distract from message delivery. In linear decks, simplicity sustains rhythm. In non-linear ones, simplicity ensures usability. The best design is one that allows the presenter to move confidently and the audience to follow effortlessly, regardless of direction.

Tools and Software Features Supporting Non-Linear Navigation

Modern presentation software increasingly accommodates non-linear flow. Hyperlinks, interactive menus, and slide-zoom features (such as zoom effect in PowerPoint) allow navigation between sections without exiting slideshow mode. These functions transform a static deck into an interactive environment. However, presenters should remember that non-linear presentation tools do not replace communication skills. Non-linearity succeeds only when the human element, the speaker’s clarity and adaptability, drives it.

Device Integration and Audience Interaction

Touchscreens, tablets, and remote controls offer physical freedom to navigate slides dynamically. Some presenters integrate polling tools or live feedback systems that determine which topic to cover next. While such interactivity can enhance audience engagement, it also introduces unpredictability. Technical reliability and rehearsal remain vital. Each digital layer adds complexity, and the presenter must retain control regardless of device or software conditions.

The Minimalist Principle

Technical sophistication does not equal effectiveness. Many outstanding nonlinear presentations rely on simple hyperlink structures or clearly labeled navigation hubs; hence why Prezi remains relevant in the presentation software niche. The model’s success depends on cognitive clarity, not graphical spectacle. Presenters should prioritize smooth transitions, stable performance, and coherent organization. Excessive interactivity risks shifting the focus from the message to the mechanics.

Common Mistakes

Confusing Flexibility with Improvisation

A non-linear presentation must never feel improvised. Flexibility means controlled adaptation within a structured system. Improvisation without structure results in fragmentation. Every pathway should lead to meaningful conclusions, and each section must stand on its own. Presenters who rely solely on spontaneous jumps appear unprepared and risk losing authority.

Overloading the Interface

In both presentation types, visual clutter undermines comprehension. Non-linear decks are particularly vulnerable because they often include navigational elements. Overcrowding the screen with icons, menus, or links creates a distraction. Navigation should be intuitive and secondary to content. The same applies to linear decks: too many transition effects or text-heavy slides diminish focus and pacing.

Ignoring Audience Orientation

Audiences can become disoriented if they lose track of progression. In linear decks, this happens when the presentation lacks clear signposting, for example, skipping sections without explanation. In non-linear decks, it occurs when navigation is abrupt or when the presenter fails to recontextualize after each jump. Continuous orientation cues are essential: short verbal summaries, consistent visual markers, or progress indicators maintain alignment.

Neglecting Time Management

Non-linear flexibility can extend beyond scheduled limits. Without strict time awareness, presenters may wander into tangents excessively. Always monitor duration, and prepare a visual or mental clock to ensure closure within the allotted period. In linear decks, over-rehearsal sometimes leads to monotony. Balance structure with energy to avoid mechanical delivery.

FAQs

What is the key difference between linear and non-linear presentations?

A linear presentation follows a fixed, sequential order from start to finish. A non-linear presentation allows flexible navigation between sections, adapting to audience interaction or contextual needs.

Which type is easier for beginners?

Linear presentations are generally easier because they provide a predetermined path and predictable timing. Non-linear formats demand experience, quick thinking, and strong content mastery.

Can a presentation combine both styles?

Yes, hybrid structures are common. A presenter may begin linearly to establish context, then switch to a menu-driven system for discussion. The transition should be clearly explained to preserve orientation.

Does non-linear always mean interactive?

Not necessarily. Interactivity is optional. Non-linear means the content can be accessed in various sequences. A presenter may still control navigation without audience input.

How can I decide which format suits my purpose?

Consider the presentation’s objective and audience behavior. If clarity, pacing, and narrative buildup matter most, use a linear structure. If adaptability, exploration, or dialogue are priorities, adopt a non-linear approach.

What are the risks of non-linear presentations?

Main risks include loss of coherence, technical errors, and uneven coverage of key points. These can be mitigated through careful design, rehearsal, and backup plans.

Can non-linear presentations be printed or shared easily?

No. Their effectiveness relies on interaction. When exported as static documents, they lose navigational context. For distribution, convert to a linear summary or written report.

Are non-linear presentations suitable for large audiences?

Usually not. Large audiences expect a shared path. Non-linearity works better for workshops, sales meetings, or small-group sessions where dialogue is possible.

Do non-linear presentations require specific software?

Most mainstream software supports them, but success depends more on design clarity than on technical features. Simple hyperlink systems can achieve strong results.

Final Words

Choosing between linear and non-linear structures is a strategic decision rather than a stylistic preference. Each model reflects how a presenter manages time, narrative, and audience engagement. Linear presentations provide order and stability. They excel when clarity and pacing take priority.

Non-linear presentations introduce flexibility and interaction, supporting adaptive discussions and personalized storytelling. The best presenters master both, selecting the appropriate structure for the occasion rather than rigidly adhering to one model.