No matter how prepared or spontaneous it was, every presentation ends the same way: with feedback. It might come immediately after the session, through body language during the talk, or later through formal evaluations. For a presenter, feedback is the most direct evidence of how an idea landed. When handled well, it becomes the foundation for measurable improvement. If ignored, it leads to repetition of the same mistakes or loss of valuable strengths.

This article covers both ends of the spectrum, negative and positive, and how to use them as part of a single learning loop. Negative comments reveal blind spots; positive ones expose what works. Together, they form the most accurate mirror of your presentation skills.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Presentation Feedback as Data

- Working with Negative Feedback

- Working with Positive Feedback

- Integrating Positive and Negative Feedback into a Single Growth Loop

- Managing Feedback in Team and Client Settings

- Developing Feedback Literacy as a Presenter

- Turning Feedback into Presentation Strategy

- FAQs

- Final Words

Understanding Presentation Feedback as Data

Feedback, at its core, is information about perception. It tells you how your audience decoded your message, how well your structure supported comprehension, and whether your delivery style inspired trust. The challenge lies in treating it as data rather than judgment.

Instead of dividing comments into “good” and “bad,” see them as variables describing performance. If multiple people mention confusion, that’s a signal of cognitive friction. If several praise your clarity, that identifies a repeatable strength. The key is not to defend or dismiss but to extract patterns.

Why Presenters Misread Feedback

Many presenters interpret comments through emotion rather than analysis. Praise inflates confidence; criticism triggers defensiveness. Both distort learning. A neutral stance, recording remarks before reacting, helps reveal what’s truly being said. This emotional regulation forms the foundation for accurate self-assessment.

Working with Negative Feedback

Negative feedback in presentations hurts because it touches identity. Even seasoned professionals experience a physical reaction: tightened chest, quickened pulse, defensive thoughts. The mistake is assuming that this discomfort equals truth. The first discipline is restraint: avoid responding immediately. Thank the person, take notes, and allow time for the emotional intensity to fade before evaluation.

Decoding Intent

Not all criticism has the same origin. Some people want to help you improve; others want to protect an organizational goal or assert authority. Before reacting, identify the likely motive. When feedback aims to align expectations or clarify objectives, it’s valuable even if poorly phrased. When it’s driven by ego or bias, extract only the useful content and discard the rest. Context gives feedback for a presentation its proper weight.

Separating Delivery from Content

Tone often distorts message reception. A client’s frustration or a supervisor’s impatience can make a valid critique feel like an attack. Strip the delivery of emotion and read for meaning. Ask: What does this reveal about how my message was received? For instance, “Your slides were confusing” may really mean the visual hierarchy failed to guide attention. The phrasing is abrasive, but the insight is still usable.

Recommended lecture: How to Create a Slide Deck

Identifying Actionable Elements

After the first reading, translate each critique into a concrete behavior or design variable you can modify. Replace “You lost the audience halfway” with “I need to adjust pacing between sections” or “I’ll add a transition summary at minute ten.” By reformulating comments into observable terms, you move from helplessness to control.

Finding patterns and blind spots

Collect written notes or transcripts of verbal feedback. Code them by theme: structure, delivery, design, audience engagement, and technical accuracy. Look for clusters. When similar issues appear across different audiences, that’s evidence of a systemic weakness. For example, if several people struggle to follow your data slides, the problem is not an isolated opinion; it’s the design or sequencing.

Rebuilding confidence

The period after receiving harsh feedback on a presentation can feel destabilizing. You may question competence or lose enthusiasm. The remedy is structured reflection. Write a brief summary of what the critique revealed, what you plan to change, and what strengths you’ll preserve. This anchors the perspective. Confidence rebuilt through analysis is more substantial than confidence built on praise alone.

Working with Positive Feedback

Positive feedback in presentations is often treated as emotional reward, but it’s primarily informational. Each compliment identifies a method or choice that succeeded. “Your examples clarified the data” indicates effective storytelling; “Your voice modulation kept us engaged” confirms delivery strength. Record these observations as data points for what to repeat.

Avoiding Complacency

When success becomes comfortable, growth halts. Praise can lead presenters to assume mastery. The goal is to turn satisfaction into a baseline, not a finish line. After every presentation, ask: Which strengths received recognition? Can they be refined or adapted for different audiences? The objective is to maintain momentum without arrogance.

Filtering Genuine Feedback from Courtesy

In professional contexts, politeness often dilutes authenticity. Generic comments like “Great job” or “Very professional” lack diagnostic value. Seek specifics. Genuine positive feedback refers to identifiable actions, how you structured an argument, used visuals, or managed Q&A. If comments are vague, request clarification: “Could you tell me which part stood out most?” This transforms flattery into insight.

Analyzing Patterns of Success

Gather feedback about the presentation into categories mirroring those for negative remarks. Identify recurring mentions of clarity, visual appeal, or pacing. When the same qualities appear across projects, they define your signature strengths. Understanding these patterns allows deliberate reinforcement. For example, if audiences often highlight clarity, study your process of simplifying information; perhaps it’s your natural comparative advantage.

Recommended lecture: How to Present Complex Concepts

Inviting Constructive Praise

Audiences rarely volunteer detailed compliments. Prompt them. After a meeting, instead of asking, “Was it okay?”, pose targeted questions:

- “Which part helped you grasp the topic best?”

- “Was there any slide that simplified the message for you?”

- “What part felt most engaging?”

These questions guide others to supply granular feedback you can use to codify excellence.

Gathering Feedback After Your Presentation

The best time to capture authentic impressions is immediately after your talk, while the content is still fresh in your audience’s mind.

You can distribute a short survey or feedback form asking attendees to rate aspects such as clarity, structure, visuals, and delivery.

Tools like Google Forms, Microsoft Forms, Mentimeter, or Slido make it easy to collect both quantitative ratings and open comments. These tools help you gather feedback through surveys or digital forms. In some cases, it worth to send an email to participants with a few questions to gather feedback about the presentation. If you use digital form tools, you can send an email to collect responses in a structure way. You can use a free presentation evaluation form email template to grab some ideas.

As an example, MailModo provide this feedback collection email in which several

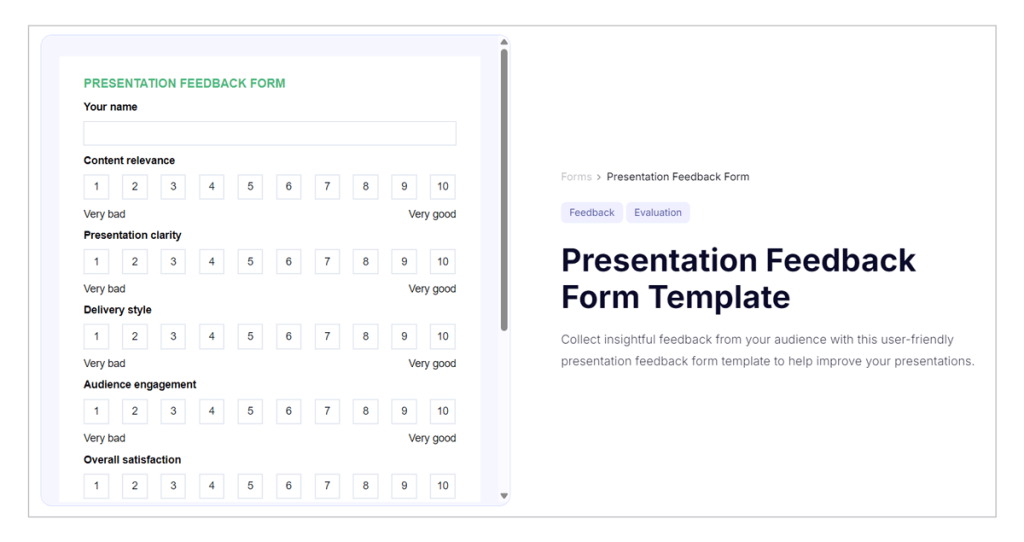

Here is an example on how you can organize the questions to gather feedback through surveys or digital forms:

Section 1: Presentation Content

- Content relevance – How relevant was the content to your needs or interests? (1–10)

- Presentation clarity – How clear and understandable was the presentation? (1–10)

- Depth of content – Was the level of detail appropriate for the audience? (1–10)

- Use of examples or visuals – How effectively did the presenter use visuals or data to support key points? (1–10)

Section 2: Delivery and Engagement

- Delivery style – How engaging was the presenter’s delivery (tone, pacing, confidence)? (1–10)

- Audience engagement – How well did the presenter maintain your attention or encourage participation? (1–10)

- Slide design – How clear and visually appealing were the slides? (1–10)

- Time management – Did the presentation fit well within the allotted time? (1–10)

Section 3: Impact and Takeaways

- Key takeaways – How valuable were the insights or lessons learned? (1–10)

- Applicability – How likely are you to apply something learned from this presentation? (1–10)

- Overall satisfaction – How satisfied are you overall with the presentation? (1–10)

Section 4: Open Feedback

- What was the most effective part of the presentation?

- What could be improved for future sessions?

- Any additional comments or suggestions?

- Would you attend another presentation by this speaker? (Yes / Maybe / No)

Gathering this data right after the session ensures higher response rates and more reliable insights for improvement.

Integrating Positive and Negative Feedback into a Single Growth Loop

Negative and positive feedback are not opposites but halves of a single system. One exposes problems; the other highlights solutions already in use. When analyzed together, they form a full diagnostic map. For instance, if negative comments target unclear transitions while positive ones praise narrative flow, the takeaway is not contradiction but refinement: transitions need to match the storytelling quality already recognized.

Building a Post-Presentation Workflow

After each event, schedule a structured debrief:

- Collection: Gather all forms of feedback, such as emails, chat messages, verbal comments, and surveys.

- Classification: Separate remarks into positive and negative, then assign categories (content, visuals, delivery).

- Analysis: Identify recurring points within each category.

- Action plan: Select no more than three improvement targets and two reinforcement targets.

- Documentation: Log the date, audience type, and results in a presentation journal.

This workflow turns random commentary into a continuous performance database.

Tracking Measurable Change

Set observable metrics: reduced confusion in Q&A sessions, higher client approval on proposals, and shorter meeting durations with the same outcomes. Over time, correlate these metrics with adjustments made from feedback. Quantifying progress transforms improvement from vague intuition into concrete evidence of mastery.

Emotional Neutrality and Long-Term Stability

Presenters who treat every comment, praise or critique, as neutral input remain emotionally steady. They neither crumble under criticism nor become complacent after success. This neutrality is learned through repetition. Each cycle of presentation, reflection, and adjustment reinforces detachment from ego and attachment to learning.

Using Feedback to Adapt Style, Not Identity

Feedback should refine technique without erasing individuality. If an audience suggests being “more formal,” interpret that as situational guidance, not a rejection of your voice. The goal is adaptability: maintaining authenticity while meeting context expectations. Versatility grounded in feedback awareness produces credibility across diverse environments.

Managing Feedback in Team and Client Settings

Encouraging a feedback culture

In team presentations, collective improvement depends on shared vocabulary. Introduce short debrief rituals after client meetings. Ask each member to note one strength and one area for refinement observed in another presenter. Keep tone factual, not personal. Over time, this practice normalizes open critique and removes stigma from negative comments.

Handling Conflicting Opinions

When multiple stakeholders provide opposing advice, “be more detailed” versus “simplify”, revisit your original objective and primary audience. Which feedback better supports your goal? Prioritize alignment over consensus. Trying to please everyone dilutes clarity.

Communicating Your Response to Feedback

Clients and supervisors notice whether their input leads to visible change. Implementing suggestions promptly signals professionalism. Even if you disagree, acknowledging receipt and explaining your rationale for alternative choices maintains trust. For example: “I considered shortening the introduction as you suggested, but the technical overview proved necessary for clarity.” This demonstrates active listening without blind compliance.

Developing Feedback Literacy as a Presenter

Understanding the mechanics of constructive critique improves receptiveness. When you practice offering balanced, specific feedback to colleagues and name behaviors rather than traits, you internalize the same evaluation standards for yourself. It builds internal calibration: you begin to assess your work using objective criteria rather than emotional reactions.

Recording Feedback Evolution

Keep a long-term feedback log. Each entry should include:

- Date and context of presentation

- Audience type

- Key positive themes

- Key negative themes

- Actions taken

- Outcomes observed next time

After a year, patterns reveal themselves: recurring blind spots, evolving strengths, areas of stagnation. This meta-analysis transforms feedback into longitudinal insight.

Preparing Psychologically Before Feedback Sessions

Before requesting evaluation, set mental boundaries. Remind yourself: “Feedback is description, not definition.” This phrase helps prevent defensive posture and encourages curiosity. Anticipate that every session will include a mix of insight, misunderstanding, and bias. Your task is to harvest the useful portion without emotional noise.

Turning Feedback into Presentation Strategy

If audiences mention confusion mid-presentation, redesign your presentation structure: add signpost slides, preview key takeaways, or insert presentation summaries. If they praise engagement, study the timing or phrasing that caused it and integrate similar cues earlier in the talk. Every change should respond directly to documented audience data.

Comments about cluttered slides suggest overloading or weak contrast. Positive reactions to slide clarity highlight effective color hierarchy or typography. Systematically apply these insights: limit text density, increase white space, and test readability on different screens before delivery.

Recommended lecture: The 10/20/30 Rule of Presentations

Pay attention to feedback on tone, pacing, and body language. If several people note that you spoke too fast during Q&A, rehearse under timed conditions with deliberate pauses. If they mention a strong presence, identify what created it, eye contact, grounded stance, steady breathing, and reinforce it consciously.

FAQs

How can I tell if feedback reflects personal bias rather than objective assessment?

Ask for clarification that links the feedback to observable elements: a slide, phrase, or gesture. Objective comments reference behavior; biased ones target traits. Keep a record of repeated patterns; if multiple people identify the same issue, it’s likely real. One-off, emotionally charged remarks often reflect bias or projection.

Should I record my presentations to compare feedback with what actually happened?

Yes. Recordings provide the context behind audience reactions. They expose moments where perception diverged from intent, such as pauses misread as uncertainty or confident gestures mistaken for dominance. Reviewing footage helps you correct misconceptions and measure alignment between feedback and reality.

How can I encourage quiet participants to give feedback?

Offer private or anonymous feedback channels after the session: forms, emails, or surveys. Some attendees feel intimidated speaking publicly, but provide valuable detail when writing. Always include open-ended questions like “What part was least clear?” or “What helped you stay engaged?” to capture thoughtful responses.

What if my manager’s feedback conflicts with client reactions?

Cross-check both against your main objective. Internal reviewers focus on brand tone or compliance; clients care about clarity and relevance. When feedback diverges, choose alignment with your presentation’s purpose and key decision-maker. Compromise strategically; don’t dilute clarity to satisfy conflicting preferences.

How do I keep feedback sessions from turning defensive or awkward?

Announce beforehand that your goal is continuous improvement. Listen without interruption and resist explaining yourself mid-session. Taking notes silently signals openness. When you respond later, focus on adjustments, not justification. Professional composure invites more useful, candid future feedback.

How do I adapt to feedback styles across different cultures?

Cultural norms shape tone and directness. Some cultures soften critique through praise; others are straightforward to the point of bluntness. Learn these tendencies and read between the lines. A “good job” might mask dissatisfaction; a “needs work” could mean a simple adjustment in expectations. Always ask for examples to anchor meaning.

How soon after a presentation should I request feedback?

Within 24 hours. The memory of your delivery fades quickly. However, avoid asking immediately after a tense or high-stakes session; people need time to reflect. Wait a few hours, then reach out with structured questions to get details while impressions remain fresh.

What’s the best system to track improvement based on feedback?

Use a feedback log or spreadsheet. Include columns for date, audience, main goals, positive themes, negative themes, actions taken, and outcomes. Review quarterly to identify measurable progress or recurring issues. This transforms feedback into longitudinal performance data rather than scattered impressions.

How can I respond to feedback I disagree with without appearing defensive?

Validate the perspective first: “I understand how it could come across that way.” Then explain your reasoning if needed: “My intent was to emphasize context.” Agreeing to reassess later shows openness without surrendering authority. Respectful acknowledgment maintains trust even when you disagree.

Is it useful to compare online and in-person feedback?

Absolutely. Delivery context changes audience attention and perception. Online viewers value visual rhythm and pacing; in-person audiences notice tone and physical presence. Comparing feedback from both reveals which aspects of your performance translate universally and which require situational adjustment.

What role does peer feedback play in presentation improvement?

Peers understand your technical context better than general audiences. Their comments help refine accuracy, logic, and industry relevance. However, they may overlook accessibility or emotional tone. Combine peer input with lay-audience reactions for a complete diagnostic picture.

How can I measure whether my feedback-driven changes actually worked?

Compare new audience outcomes to previous ones: engagement levels, decision speed, or follow-up questions. If previous confusion points disappear and engagement improves, the feedback-based change succeeded. Objective indicators, shorter clarification times, better retention, and more positive Q&A validate the impact.

Final Words

Mastering presentation feedback is the mark of professional maturity. Anyone can deliver a presentation; few can transform audience reactions into a systematic learning engine. Positive and negative comments are complementary sources of truth. Praise confirms alignment; critique reveals misalignment. Together, they chart your trajectory as a communicator.

Approach each session not as judgment but as calibration. Over time, your delivery will become sharper, your content more resonant, and your confidence grounded in evidence rather than assumption.