Executives work within tight margins of time and attention. Their agendas are shaped by constant trade-offs, high-stakes decisions, and accountability for organizational direction, leaving little room for meandering or unfocused communication. When presenting to executives, the value of a message is judged almost immediately by how clearly it frames relevance and consequences. A meeting scheduled for 10 minutes often demands impact in far less time.

This article explains how to structure and deliver executive presentations that support fast, informed decision-making.

Table of Contents

- Why is an Executive Presentation a Different Presentation Type?

- Understanding the C-Suite Audience

- How to Structure an Executive Presentation

- Recommended PowerPoint Templates for Executive Presentations

- Delivery Tips for Executive Presentations

- Common Mistakes in Executive Presentations

- FAQs

- Final Words

Why is an Executive Presentation a Different Presentation Type?

An executive presentation is a different presentation type because it is designed for decision-making under severe time and attention constraints. When someone steps into a boardroom or joins a virtual meeting with a CEO or other senior leaders, attention is earned through clarity and relevance, not through detailed exposition. Although a meeting may be scheduled for ten minutes, the effective window to communicate value is often much shorter. This forces a fundamentally different approach from conventional reporting or informational presentations.

The defining question behind an executive presentation is simple: if you had only a brief moment with the CEO, what would you show first? The answer determines the structure of the entire slide deck for decision makers. Executives do not want to reconstruct meaning from raw information. They expect interpretation. Process details, methodology, and background matter only to the extent they change risk, revenue, resource allocation, or competitive position. Whenever presenting to executives, the goal is not to explain how work was done, but to clarify what the results mean and what decision they support.

This shifts responsibility onto the presenter. Content must align with the cadence of executive thinking, which is outcome-driven, interruption-tolerant, and forward-looking. Arguments must survive questioning without collapsing, and recommendations must be explicit. Executive presentations are therefore built around conclusions first, supported by selectively chosen evidence, with deeper detail held in reserve.

Strategic frameworks such as KPIs, OKRs, the Balanced Scorecard, SWOT, the McKinsey 7S model, and Porter’s Five Forces are frequently used because they compress complex realities into familiar decision-making language. Firms like McKinsey, Bain, and Deloitte reinforce this model through executive briefing formats that privilege headline-first communication. Over time, this has set clear expectations: executive presentations exist to accelerate understanding and enable action, not to document work.

Understanding the C-Suite Audience

Communicating to executives begins with understanding the cognitive environment they inhabit. Their calendars compress diverse responsibilities into narrow time slots, and every decision carries implications across departments, budgets, and markets. Presenters who understand this landscape adapt both tone and structure. Those who overlook it risk losing attention within the first minute.

Revenue, risk, strategy, and growth dominate the C-suite perspective. Operational details matter only when they change the shape of these core elements. A CTO, for example, reviews technology proposals through the lenses of scalability, risk exposure, and competitive advantage, not through implementation minutiae. A CFO listens for cost structures, forecast reliability, and the capital impact of each recommendation. The CEO, whose focus is broadest, assesses alignment with long-term direction and organizational priorities. Even the Board of Directors evaluates the material primarily through governance, risk, and strategic oversight rather than tactical execution.

This is why presenters preparing how to speak to a C-suite audience must distinguish between what is essential and what is merely descriptive. Executives want distilled insight; they do not want to reconstruct it themselves. They want the reasoning, not the procedural journey. They listen for implications and trade-offs, not status updates. This expectation also influences how they interpret slides. A dense visual suggests unclear thinking. A sprawling set of bullet points implies a lack of prioritization. A clear headline paired with a sharp visualization signals discipline and respect for their time.

Executive attention is selective rather than continuous. It shifts rapidly to areas of potential risk or opportunity. Speakers should expect interruptions and treat them as signs of engagement rather than challenges when presenting to executives. A well-structured narrative withstands these interruptions because each point is modular and anchored in a headline-first structure.

Time constraints force presenters to communicate in layers. The first layer delivers the conclusion. The second layer supports it with essential data. The third layer, often reserved for Q&A or appendices, expands into specific detail. This hierarchy matches how executive presentations are processed and evaluated in real time.

How to Structure an Executive Presentation

When speaking to leaders under intense time pressure, the order in which information appears matters as much as its content. A coherent executive presentation follows a logic that accelerates understanding.

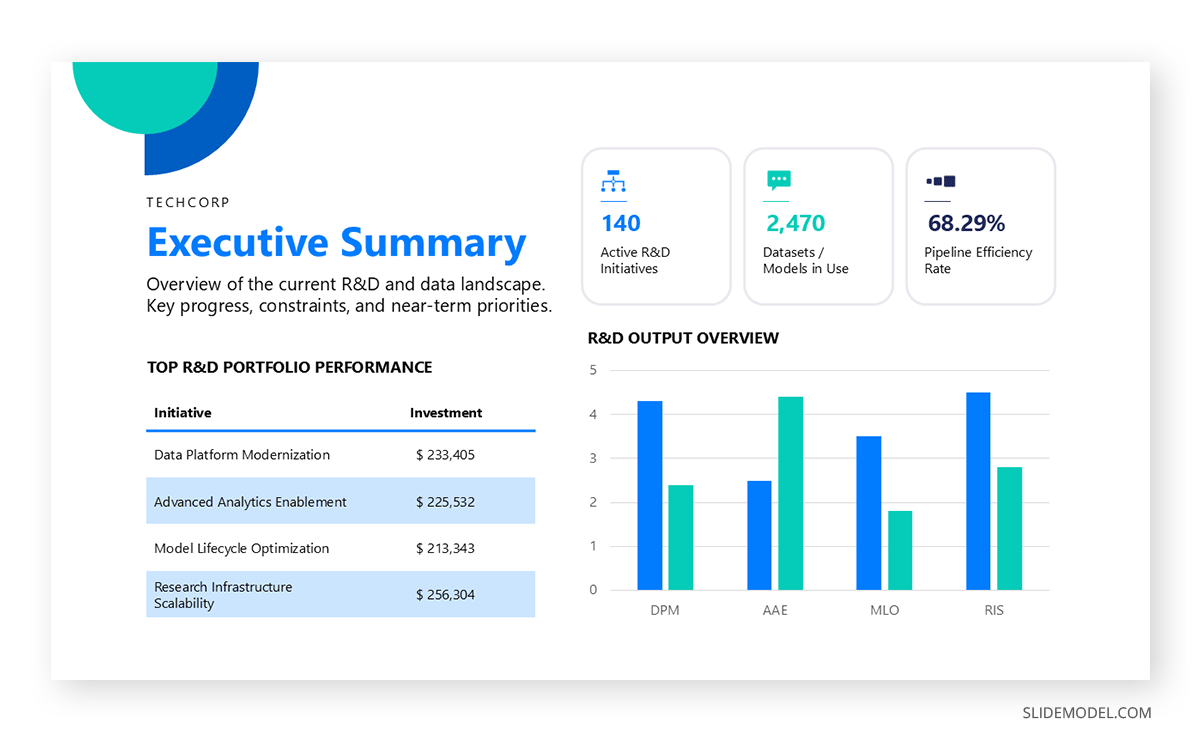

The first principle is to begin with an Executive Summary, presented in a headline-first approach. Instead of building toward the conclusion, lead with it. This mirrors the logic of the Pyramid Principle, which organizes reasoning from the conclusion to the supporting evidence rather than the other way around. Our executive summary guide demonstrates how a refined summary enables an audience to grasp the direction before hearing the details.

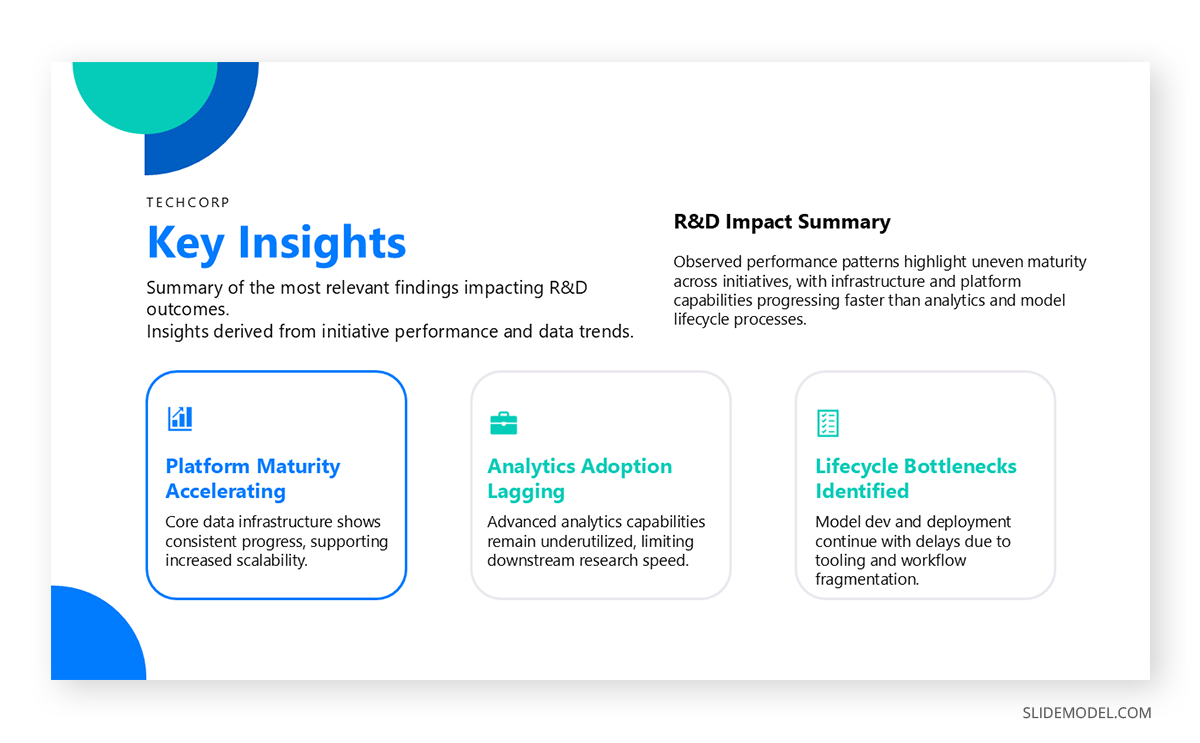

A second principle is limiting the number of core insights. Executives do not evaluate dozens of points; they assess a small set of strategic implications. The presenter’s role is to simplify complex information into one to three primary insights and use supporting materials only when questioned. A coherent sequence of account executive presentation slides anticipates this pattern and avoids unnecessary elaboration.

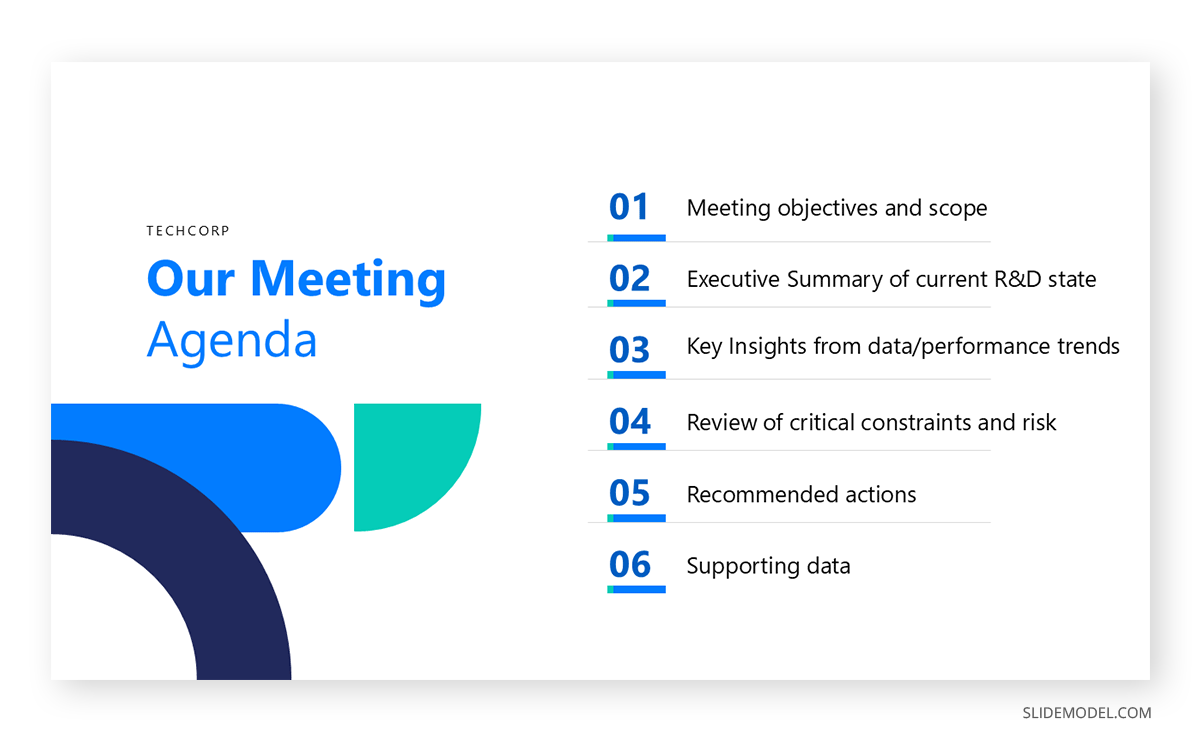

A recommended high-level structure for how to present to executives is:

Title & Objective

State the goal of the session. This prevents misalignment and reduces the risk of tangential questions.

Executive Summary

Present the conclusion or recommendation first. Summarize the insight in a single sentence and support it visually.

Agenda Slide

Present a concise list of points to be approached throughout the presentation.

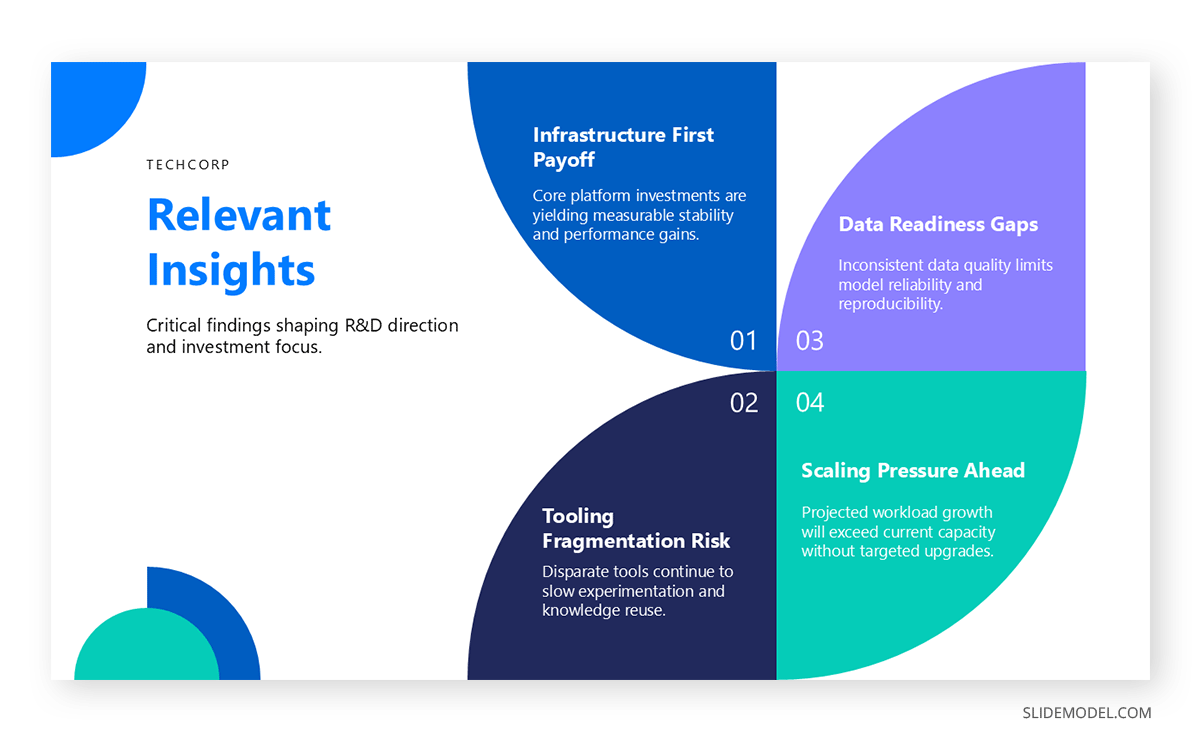

Key Insights (1–3 slides)

Each slide should contain one idea. Each insight links to a business outcome: revenue, risk, cost, timeline, or competitive position. If the meeting is tailored to a specific area, we can use up to 3 slides to present all relevant insights affecting the situation.

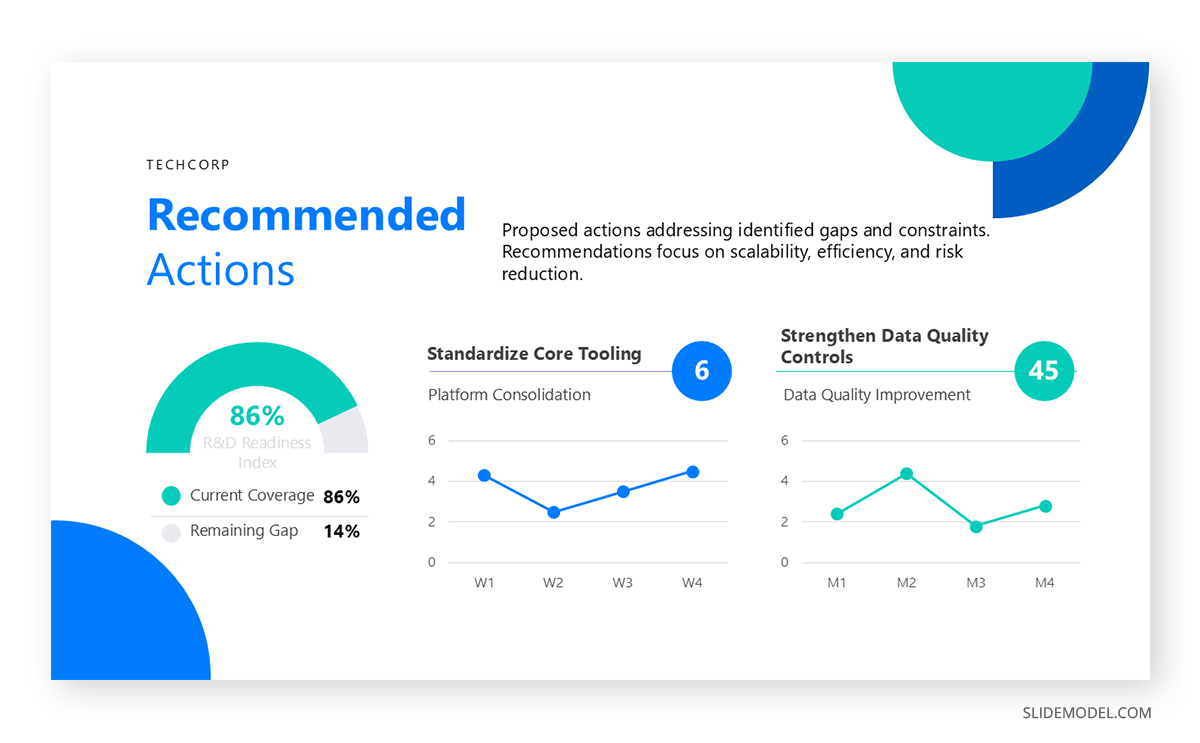

Recommended Action / Decision

Executives expect a decision request. Stating it clearly is necessary for closing the loop.

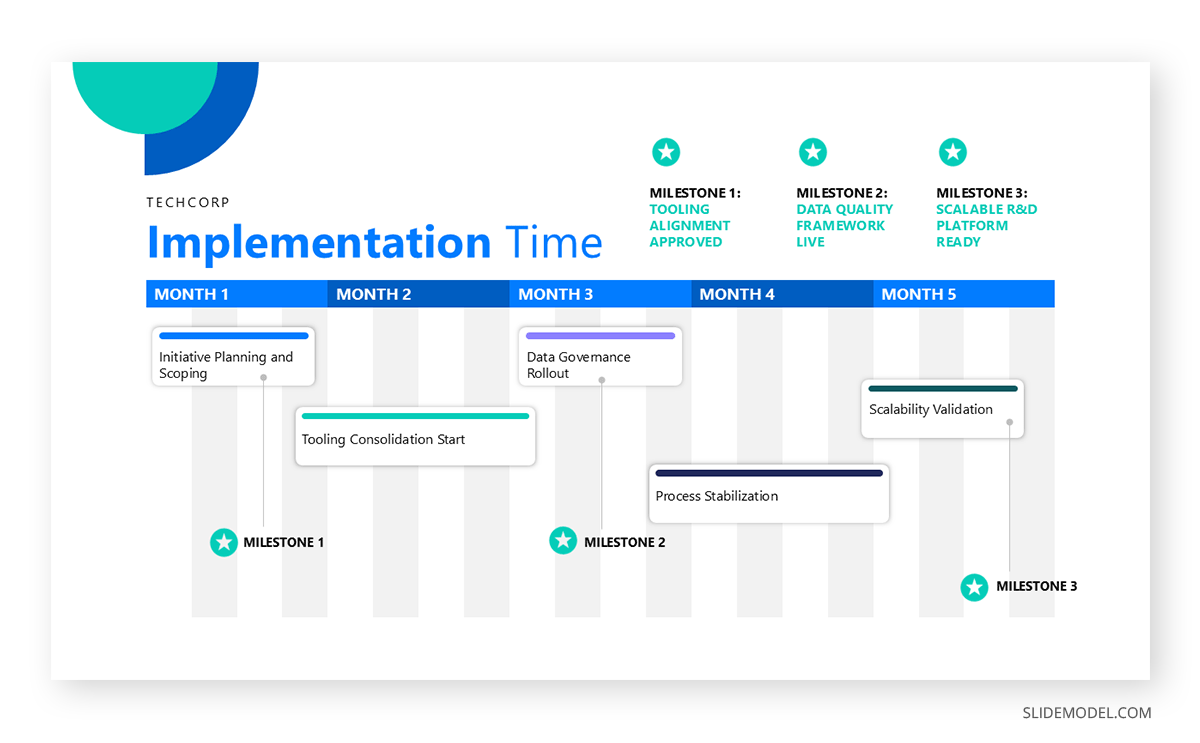

You can frame the response time for that decision using a timeline slide.

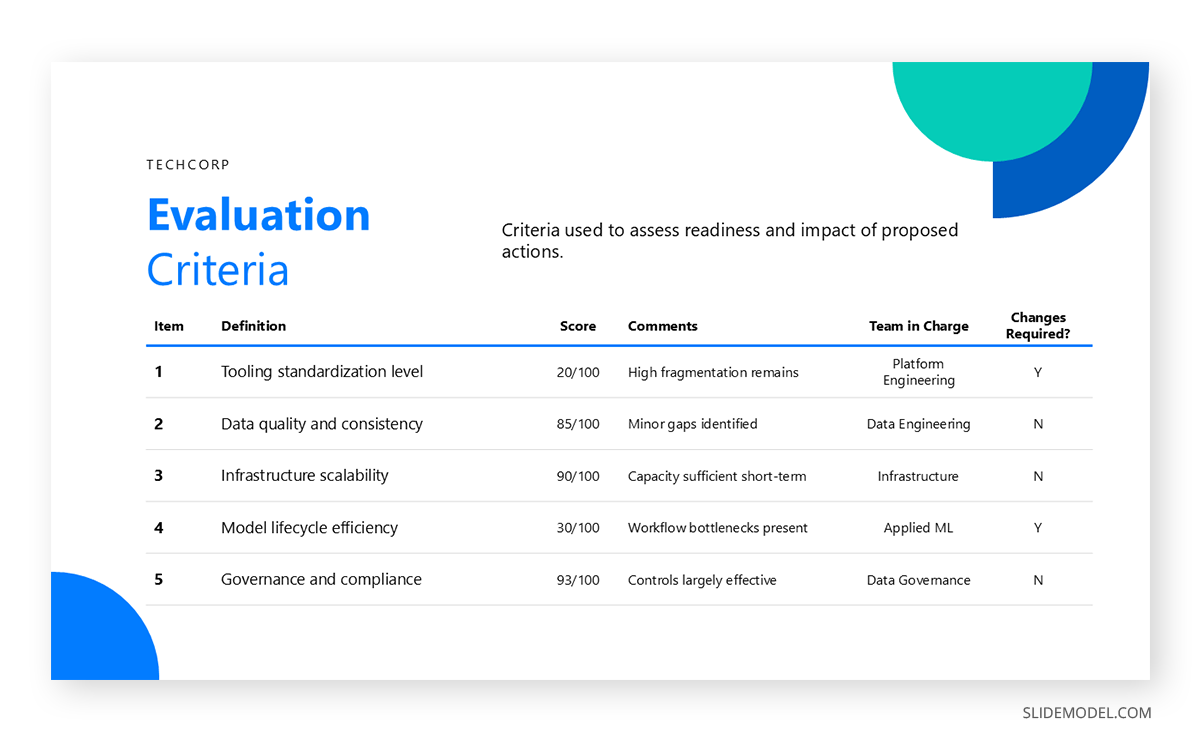

It’s also recommended to add an evaluation criteria slide so executives can see how you’ll measure the impact of your actions.

Supporting Data or Appendix

Additional slides remain accessible but not central. This respects time while equipping the presenter to answer technical questions.

This order matches that of professional consulting firms when building executive briefing presentation materials. It prioritizes orientation, then insight, then decision, then proof. A boardroom presentation adopts the same logic, though with more emphasis on governance and oversight.

The frameworks referenced earlier align naturally with this structure. Balanced Scorecard categories (financial, customer, internal process, learning, and growth) help classify insights. OKRs link recommendations to measurable outcomes. SWOT and Porter’s Five Forces help frame the external context. The McKinsey 7S model helps justify organizational implications.

Recommended PowerPoint Templates for Executive Presentations

Below is a tailored list of PowerPoint templates intended for executive presentations. Each slide design is entirely editable in PowerPoint and Google Slides.

Delivery Tips for Executive Presentations

Delivery matters as much as structure. Even the best-designed decks cannot compensate for a presenter who loses control of pacing or clarity. Executives evaluate the presenter’s command of content, not just the content itself. This is why C-suite presentation tips emphasize preparation, timing, and composure.

Time Management

Time management begins with segmenting the presentation. Allocate a strict portion to each section and rehearse transitions. A 10-minute slot may require 1 minute for the opening, 2 for the summary, 4 for insights, 1 for recommendations, and the rest for questions. These parameters protect the message from derailment. Executives frequently move directly to Q&A to pressure-test the recommendation. This should not be interpreted as impatience; it reflects their decision-making process.

Clear & Understandable Slides

Clarity is strengthened by limiting each slide to a single idea. A presenter who attempts to discuss a cluster of ideas risks diluting all of them. This guideline aligns naturally with executive summary slides, which immediately signal the dominant point. When slides follow this discipline, the presenter can summarize each in twenty seconds or less, a skill essential when meetings run ahead of schedule or executives request a compressed version.

The Power of Visuals

Visual alignment also influences delivery. Many presenters attempt to speak to fully loaded slides and struggle to maintain coherence. Using KPI dashboard PowerPoint visuals, comparative charts, or structured data arrangements helps focus the verbal explanation. Executive audiences respond more quickly to synthesis than to narration. Replace long explanations with short interpretive statements: “This variance increases exposure,” or “The trend improves margin stability.”

A Presenter’s Preparation

Confidence signals competence. This does not require a theatrical performance; it requires deep familiarity with the reasoning behind each point. Knowing how each number was derived, understanding the data’s limits, and preparing alternative interpretations allow the presenter to navigate difficult questions without hesitation.

Strong delivery also involves anticipating potential objections. For example, if presenting a cost forecast to a CFO, expect questions about assumptions, volatility ranges, and risk buffers.

Common Mistakes in Executive Presentations

Overloaded Slides

One frequent mistake is overloading slides with data. When too many numbers compete for attention, none appear important. This also forces executives to parse information themselves, which contradicts the purpose of an executive-level presentation. Data volume should reflect relevance, not availability. Supporting evidence belongs in the appendix, not in the main narrative.

Delaying the Conclusion

Another problem is burying the conclusion. Presenters accustomed to academic or operational reporting often place their key message at the end of the deck. This structure fails in executive environments, where time is limited and interruption is expected. A delayed conclusion creates uncertainty and encourages premature questioning.

Technical Language Overuse

Unnecessary jargon also disrupts comprehension. Executives are knowledgeable, but not equally versed in every discipline. A presentation about engineering resources should be understandable to a CFO; a marketing strategy should be interpretable to a CTO. If a term does not contribute directly to comprehension, omit or explain it. Technical detail belongs in Q&A or supplementary slides.

Misalignment Between Recommendations and Business Outcomes

Failing to connect recommendations to business outcomes is another common issue. Executives respond to reasoning that maps actions to consequences. A proposal lacking operational, financial, or strategic implications appears incomplete. Presenters must demonstrate how their insight changes risk, opportunity, cost, or capacity.

FAQs

What makes an executive-level presentation different from a standard business presentation?

An executive session prioritizes conclusions over process. Leaders expect the core recommendation first, supported by only the data necessary for a decision. Structure, brevity, and clarity outweigh narrative detail.

How should I structure an executive summary slide?

State the conclusion first, followed by one or two high-impact insights and a clear decision request. This mirrors how executives scan information during executive presentations.

How do I decide what to include in a slide deck for decision makers?

Include only material that changes a decision, reflects risk, or affects outcomes. Supporting content moves to the appendix unless requested.

What are the most important C-suite presentation tips for timing?

Limit the opening, deliver your summary immediately, and reserve space for questions. Executives often shift directly into discussion, so the narrative must hold up even when interrupted.

How can I prepare for questions from the CEO, CFO, COO, CTO, or CMO?

Know the assumptions behind each metric, understand the financial and operational implications, and prepare alternative scenarios. Leaders test reasoning, not slides.

How do I avoid overwhelming executives with information?

Use one idea per slide, headline-first structure, and focused visuals. Tools like KPI dashboard PowerPoint templates help reduce noise and highlight patterns.

What role do frameworks like KPIs, OKRs, SWOT, or the Balanced Scorecard play?

They provide a structured language executives already understand, making it easier to communicate alignment, trade-offs, and strategic impact during a boardroom presentation.

What is the biggest mistake presenters make when communicating with executives?

Delaying the conclusion. Executives expect immediate orientation. If the key message appears late, the presentation loses momentum and clarity.

Is it acceptable to skip process explanations entirely?

Process appears only when it changes the risk profile or strengthens trust. Otherwise, leave it for the appendix or Q&A.

Should presentations to the Board of Directors differ from presentations to individual executives?

Board sessions usually emphasize governance, risk, and strategic oversight. A board presentation template supports this by prioritizing these categories.

How can I practice speaking at an executive pace?

Reduce each slide to a 20-second explanation. If it cannot be explained quickly, the slide contains more than one idea.

Final Words

Presenting to executives is not about impressing them with exhaustive detail. It is about equipping them to make decisions efficiently. A strong CEO presentation, a concise strategic update, or a focused executive briefing presentation delivers clarity faster than the audience expects. The structure, visuals, and delivery all serve the same purpose: reduce cognitive load while maintaining analytical depth.

When presenters understand how to shape their material for leaders under time pressure, they gain influence. They frame insights around implications, restrict content to what supports the central recommendation, and anticipate questions that test assumptions. They leverage templates, dashboards, and AI-assisted design tools to refine the message rather than work through formatting obstacles.