Return on Investment holds a distinct place in client presentations because it functions as both a metric and a decision-making tool. Clients do not evaluate ROI as a technical detail; they assess it as an argument about where their resources should go. Presenters who understand this treat ROI not as a final slide, but as a thread woven through the presentation’s logic. Every assumption, action, and outcome relies on the audience seeing a clear relationship between cost, effort, and measurable return.

This article examines how to present ROI to clients in a way that supports decisions rather than overwhelms them with figures. The aim is to convert ROI from a numerical result into a concrete story of value, framed with discipline, transparency, and confidence.

Table of Contents

- Why ROI Shapes Client Decisions

- Clarifying the Type of ROI You’re Presenting

- Tracing the Path From Investment to Outcome

- Designing ROI Evidence on Slides

- Explaining ROI Variability, Constraints, and Causality

- Handling Objections and Questions About ROI

- FAQs

- Final Words

Why ROI Shapes Client Decisions

Return on Investment appears in almost every business conversation, but its importance is often misunderstood. Clients do not ask for ROI because they want a number. They ask for reassurance that the path ahead is justified. ROI compresses complexity into a format they can compare across strategies, vendors, or internal alternatives. A presenter’s responsibility is not only to calculate ROI but to reveal the reasoning that supports it. When presenting ROI to clients, the objective is not persuasion by optimism but clarity of reasoning.

Recommended lecture: How to Present Complex Concepts

For most audiences, ROI represents control. A client wants to feel that an investment is not a leap of faith. Even if the return is uncertain, the structure behind the prediction must be rational. That perception of structured thinking stems from how the presenter discusses assumptions, relationships, and risk management. When that structure is absent, even a positive ROI fails to instill confidence.

Clients also use ROI as a filter. They separate what is essential from what is merely attractive. By grounding decisions in return expectations, they avoid emotional or aesthetic bias. A clear ROI explanation helps the presenter channel attention toward impact rather than features.

Another reason ROI matters is that it represents alignment between the presenter and the audience. When ROI is well-presented, it signals that the presenter understands the client’s priorities. If the presentation focuses on the presenter’s internal achievements or technical sophistication without connecting them to return, clients perceive a gap in understanding. On the other hand, when ROI is integrated seamlessly, it reinforces that both sides evaluate success under the same criteria.

Recommended lecture: Audience Engagement

The influence of ROI grows further when decisions involve long timeframes or large capital commitments. In those cases, clients measure not only potential return but also the presenter’s ability to monitor it. They assess whether the presenter can track, interpret, and communicate outcomes over time. These expectations make delivery equally important as calculation. ROI presentations are as much about illustrating future partnership dynamics as they are about reporting value.

Ultimately, ROI shapes decisions because it transforms a proposal into an argument. Clients do not respond to the figure itself; they respond to the logic behind it. Presenters who treat ROI as a communicative act, not a spreadsheet result, discover that clarity and structure create more persuasive power than optimistic projections ever could.

Recommended lecture: Data-Driven Decision Making

Clarifying the Type of ROI You’re Presenting

ROI is not a single measurement. It varies depending on sector, objective, and calculation method. Telling clients that a campaign or project “has strong ROI” is insufficient unless the nature of that return is specified with precision. Presenters need to define the type of ROI they are discussing, explain why it aligns with the client’s objective, and explain how it differs from common interpretations. Ambiguity erodes trust, while clear definitions anchor the entire narrative.

The first distinction concerns financial versus operational ROI. Financial ROI is the net gain relative to the investment. Operational ROI describes improvements in performance, efficiency, or output. Both are valid, but they serve different purposes. When the presenter does not specify the category, the audience fills the gap with their own expectations, which may not match the outcome being presented. The presenter must explicitly state what the ROI measures before interpreting them.

The second distinction involves the timeframe. ROI measured within a quarter reflects immediate impact, while ROI across a year or more accounts for long-term effects. Short-term ROI typically captures direct revenue or cost reductions. Long-term ROI incorporates strategic advantages such as retention, reputation, and infrastructure efficiency. A client interpreting a long-term process through a short-term lens will categorize the investment as weak. This misalignment is entirely avoidable when the presenter defines the horizon at the beginning of the segment.

A third distinction concerns attribution. ROI rarely originates from a single action. Campaigns depend on seasonality, audience behavior, and operational choices. Infrastructure upgrades influence multiple departments. When attribution is oversimplified, clients instinctively question the validity of the calculation. They expect a presenter to acknowledge external variables and outline how attribution was managed. This does not weaken the argument; it solidifies credibility.

Presenters should also clarify whether ROI is modeled or measured. Measured ROI reflects past performance. Modeled ROI projects expected return based on assumptions. These assumptions must be disclosed. Otherwise, projections appear speculative, weakening the perceived rigor of the analysis.

Tracing the Path From Investment to Outcome

Clients rarely object to ROI figures themselves. More commonly, they object because the connection between investment and outcome feels unclear. A high ROI with a weak causal explanation is less persuasive than a moderate ROI supported by a well-structured, evidence-based narrative. Presenters must trace, step by step, how resources were transformed into results without overwhelming the audience.

This explanation begins with an investment breakdown. Compelling ROI storytelling depends on making causal links visible rather than implied. The presenter specifies what the client contributed: financial capital, labor, time, or access to resources. This transparency prevents confusion about what constitutes cost. When presenters skip this step, clients frequently misinterpret ROI as inflated or incomplete. A clear investment baseline also provides a reference for future comparisons.

Next, the presenter illustrates the mechanism of return. This mechanism should not be portrayed abstractly. Clients expect to see concrete pathways showing how the investment led to the outcome. For example, a marketing investment may yield returns through increased conversion efficiency, higher lifetime value, or lower acquisition costs. An operational investment may generate a return through time savings or reduced errors. If the mechanism is not named, the connection appears assumed rather than demonstrated.

The third step is linking actions to metrics. ROI depends on metrics behaving as expected, but audiences accept this link only when the presenter explains it logically. If a process improvement decreased cycle time by a measurable amount, that time-saving must be linked to financial value. If a campaign increased qualified leads, its contribution to revenue must be explained.

Presenters should respect cognitive load. The path from investment to return should be simple enough to understand without extensive recalculation. When necessary, use a brief bulleted list to show the causal chain:

- Investment

- Mechanism

- Metric effect

- Financial or operational outcome

This is one of the few moments where bullets serve clarity rather than decoration. The list becomes a structural map, not a stylistic crutch.

The final step involves demonstrating proportionality. Clients want to see that the return is appropriate relative to the scale of the investment. A small return on a massive cost may still have strategic value, but the presenter must articulate that value clearly. Conversely, a large return on minimal investment appears compelling but must be framed responsibly to avoid accusations of overselling.

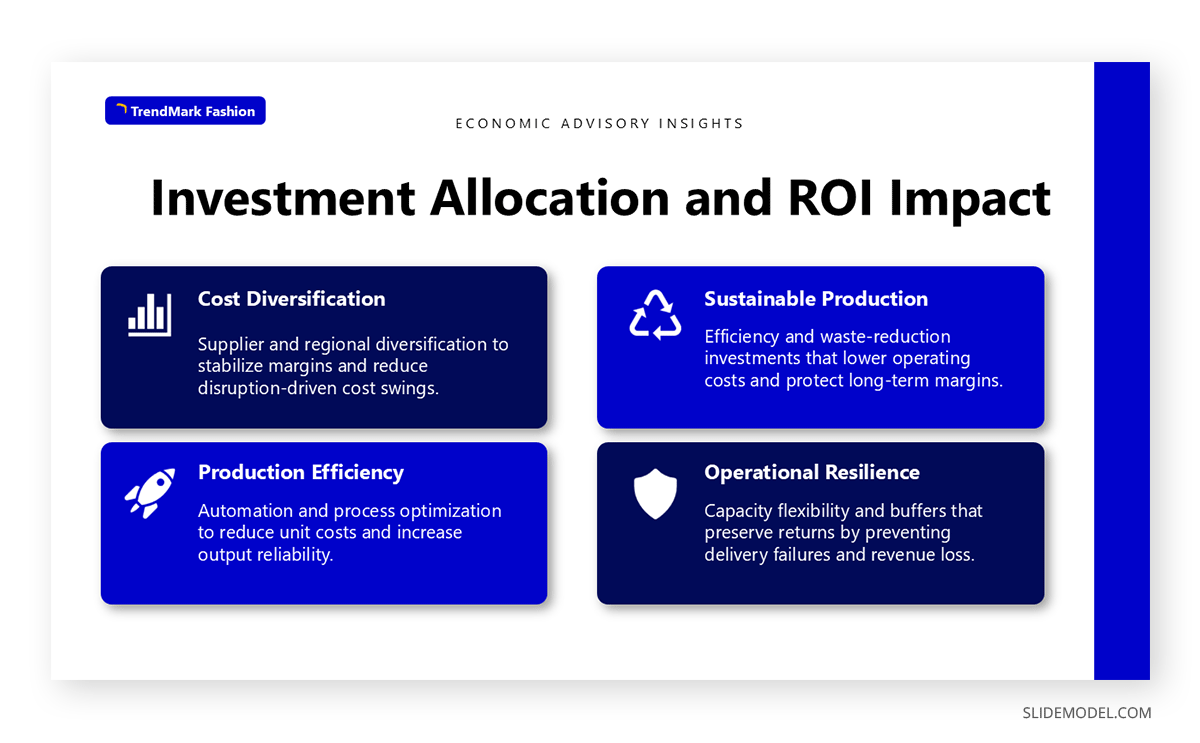

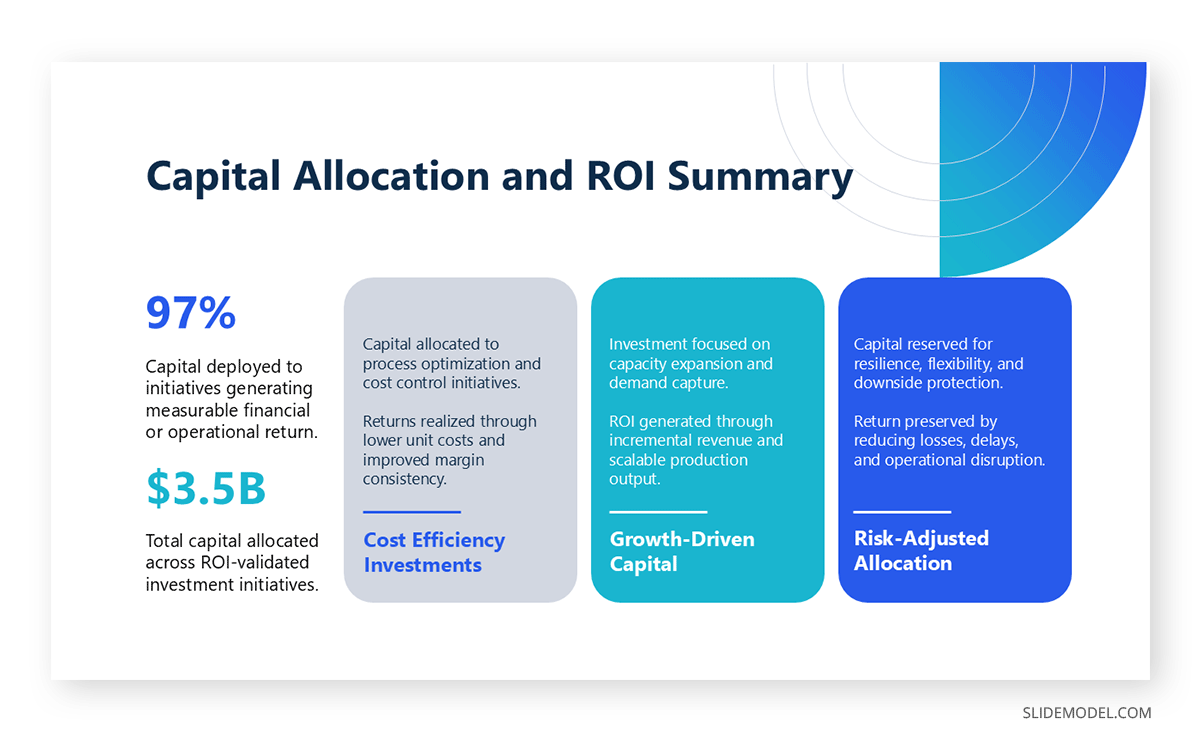

Designing ROI Evidence on Slides

ROI is not intuitive for most audiences. Visual presentation influences how clients interpret its meaning, precision, and relevance. Slides should help decode ROI, not complicate it. The principles that guide key metric presentations apply here as well: hierarchy, clarity, consistent formatting, and restraint in design choices.

Well-structured ROI slides reduce interpretive effort and allow clients to focus on meaning rather than mechanics. The primary figure must be immediately visible. This typically involves placing the ROI value at the top or center of the slide, using scale and contrast rather than color saturation. Excessive embellishment weakens cognitive clarity. Clients want to see structure, not decoration.

Context is equally important. ROI must appear with its baseline, timeframe, and calculation notes. These details should not dominate the slide, but they must be discoverable. A small sublabel can indicate the period evaluated or the cost basis used. When these details are omitted, the audience fills the gaps with assumptions, often to the presenter’s disadvantage.

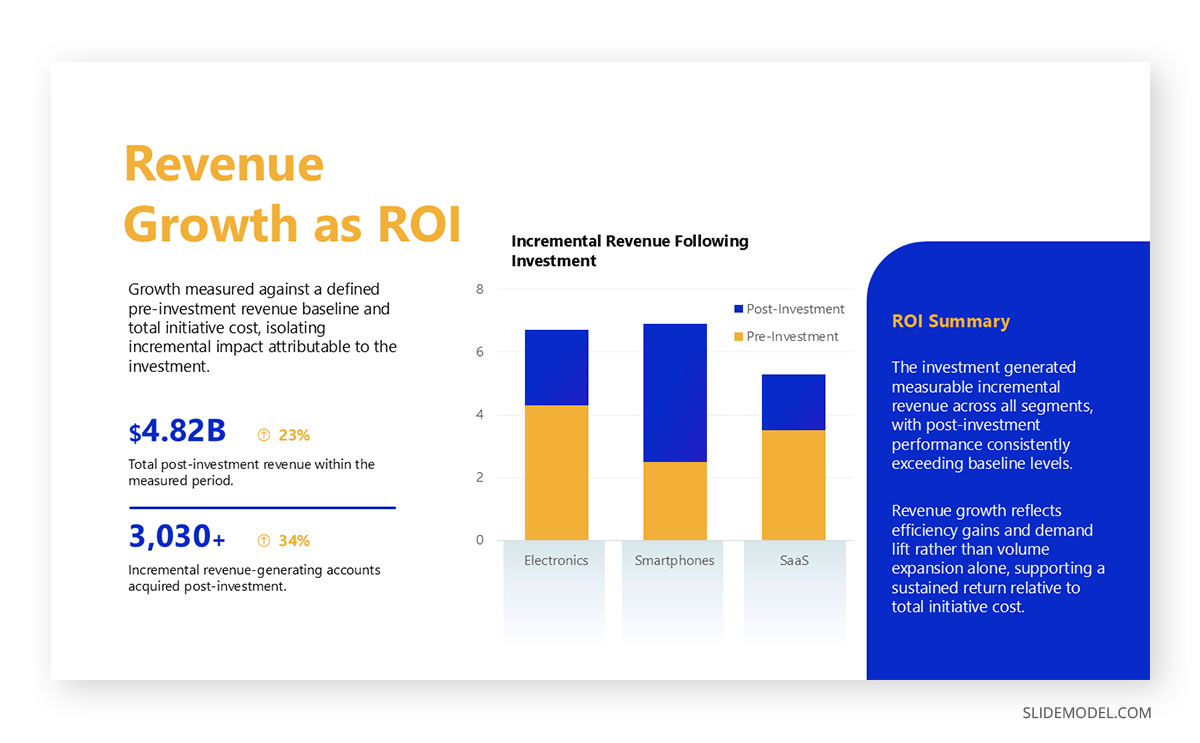

Charts should be selected based on interpretive purpose, not aesthetic preference. A bar chart is effective for demonstrating comparative returns across strategies. A line chart is effective for showing ROI trends over time. A waterfall chart is effective for explaining how various components contributed to total return. The slide should answer the client’s question as directly as possible. If the format forces interpretation effort, revise it.

Color systems require careful control. Each color must express meaning rather than stylistic intent. Presenters often choose green to represent positive ROI, but the color palette must remain consistent across the deck. When green appears in one context as profit and in another as traffic volume, the audience loses the visual mapping. Misalignment creates confusion and undermines perceptions of rigor.

Visual hierarchy also governs supporting metrics. Suppose ROI depends on three foundational figures: cost, revenue generated, and time-to-impact. These secondary metrics should appear in a stable, predictable layout. Clients scan slides. They rely on positional memory to locate recurring information. Deviations in placement or size cause unnecessary mental effort.

Explaining ROI Variability, Constraints, and Causality

ROI is never fixed. Markets change, operations shift, and assumptions evolve. Clients know this, and they evaluate presenters not only on the return achieved but on their ability to interpret variability responsibly. When presenters treat ROI as a static, unquestionable outcome, they appear unprepared for scrutiny. The audience perceives confidence as exaggeration rather than expertise.

A strong ROI presentation includes acknowledgment of variability. This does not undermine the result; it strengthens it. Variability may originate from seasonality, operational constraints, market fluctuations, or internal resource allocation. Presenters should identify the factors that exerted the greatest influence. This creates a sense of analytical rigor and demonstrates that the presenter understands the environment rather than focusing solely on the final figure. On the other hand, weak ROI justification often stems from unclear causality rather than poor performance.

Constraints must also be explained clearly. Many ROI outcomes reflect limitations the client imposed, whether budget caps, data availability, or timeline restrictions. Presenters should describe these constraints factually, without complaint or dramatization. The objective is to contextualize the return, not justify shortcomings. When constraints are framed accurately, the audience reframes its expectations and evaluates ROI more appropriately.

Causality is the core of any ROI argument. If the presenter fails to explain why the return occurred, the audience will interpret the metric as luck, coincidence, or incomplete analysis. This is where presenters must be precise. They should identify the specific elements of the strategy that influenced outcomes and demonstrate, with data, how those elements produced the observed effects.

At times, ROI may reflect mixed results: strong return in one segment, moderate in another, and weak in a third. Presenters should not hide these differences. Instead, they should explain what each variation reveals about the client’s market or process. This nuanced interpretation positions the presenter as a partner who diagnoses issues rather than someone who showcases isolated successes.

Risk assessment should also be addressed. ROI does not guarantee future performance. Clients expect presenters to articulate which factors are likely to remain stable and which may shift. The goal is not to diminish confidence but to demonstrate maturity in forecasting. A presenter who acknowledges uncertainty appears more reliable than one who predicts without restraint.

Handling Objections and Questions About ROI

ROI presentations inevitably attract questions. Clients want clarity, precision, and reassurance, and they test those qualities by probing assumptions and methodology. Much of explaining ROI to clients involves addressing uncertainty rather than defending numbers. Presenters who prepare for this dynamic communicate authority. Those who appear defensive or evasive damage credibility, even if the ROI is substantial.

Clients may challenge the attribution model. They may argue that external factors influenced performance more than the presenter accounted for. A prepared presenter acknowledges the possibility, clarifies how attribution was handled, and offers alternate scenarios without overstating precision. This maintains credibility and reinforces analytical discipline.

Another common objection concerns cost structure. Clients sometimes believe hidden costs should have been included or that specific cost categories disproportionately affect ROI. Presenters should address this calmly, explaining why particular costs were included or excluded. The explanation should remain factual rather than persuasive. Clients respond well when they see that the methodology was applied consistently.

Timeframe objections are equally frequent. A client may argue that the evaluation period was too short or too long. Presenters should justify the timeframe in relation to the client’s business cycle or the nature of the investment. If the timescale could reasonably vary, the presenter can offer alternative ROI calculations based on a different horizon. This demonstrates transparency rather than rigidity.

Some objections arise from unclear expectations. If a client expected immediate revenue but the investment produced long-term structural value, they may interpret the ROI as weak. Presenters should revisit the initial objective and reframe the result accordingly. This realignment prevents misunderstanding without appearing reactive. When ROI assumptions are left implicit, projections appear speculative rather than reasoned.

When answering questions, pacing matters. Presenters should pause before responding, maintain a steady tone, and refer to evidence rather than conjecture. Avoiding filler phrases and vague reassurances keeps the exchange grounded. Clients interpret tone as strongly as content; calm delivery signals that the presenter understands the material and welcomes scrutiny.

FAQs

How detailed should ROI explanations be in a client presentation?

Enough to clarify causality and assumptions, but not so detailed that the audience must reconstruct the calculation themselves. Provide structure, not spreadsheets. Use appendices for granular data.

Should ROI always be shown as a percentage?

Not necessarily. Some contexts require absolute return values, savings, or efficiency gains. Choose the format that best supports interpretation.

How should ROI be compared across different initiatives or vendors?

ROI comparisons are only meaningful when the same assumptions, timeframes, and cost structures are applied. Before comparing figures, ensure that each ROI is calculated using consistent baselines and that differences in scope or constraints are clearly stated. Without alignment, comparisons reflect methodology differences rather than actual performance.

What if ROI is positive but lower than expected?

Explain the constraints, identify which elements performed below projection, and outline how the next cycle can be adjusted. Clients value analytical insight more than inflated results.

Can modeled ROI appear in the same slide deck as measured ROI?

Yes, as long as they are clearly distinguished. Mixing them without labeling creates misinterpretation.

How can presenters compare ROI when one option has qualitative benefits?

Qualitative benefits should be translated into decision relevance rather than forced into numerical equivalence. When direct comparison is not possible, presenters should explain how qualitative outcomes influence long-term value, cost avoidance, or strategic flexibility, and position them alongside quantitative ROI rather than replacing it.

How should presenters communicate long-term ROI that lacks immediate impact?

By connecting ROI metrics to strategic goals and explaining why the extended horizon is necessary for value realization. Avoid oversimplifying.

Is a higher ROI always the better option when comparing alternatives?

Not necessarily. A higher ROI may involve greater volatility, greater dependence on external factors, or increased operational strain. Comparative ROI should be evaluated alongside risk, scalability, and strategic fit. A lower but more predictable return better supports long-term objectives than a higher, unstable one.

What if ROI varies across segments or channels?

Present the variation clearly. Differences often reveal important patterns. Clients appreciate honest segmentation.

Should presenters include ROI benchmarks from competitors?

Only if the comparison is reliable. Benchmarks without clear sourcing weaken credibility.

Is it necessary to visualize ROI?

Visualization improves comprehension when executed with a clear hierarchy and minimal clutter. Poor visual design, however, reduces trust.

Can ROI be combined with qualitative impact statements?

Yes. Qualitative outcomes can contextualize quantitative return, especially in long-term or strategic investments.

How should presenters respond when clients question the validity of assumptions?

By explaining the reasoning behind each assumption, offering alternative scenarios, and demonstrating that the methodology holds under variation.

Final Words

Presenting ROI to clients is about guiding decisions, not defending numbers. A clear ROI narrative gives clients the structure to assess value, risk, and next steps with confidence. When assumptions are explicit and causality is explained, ROI becomes a shared reference point rather than a point of friction. The presenter’s role is not to amplify results, but to make them intelligible and actionable.

Well-presented ROI also reinforces accountability. It shows that outcomes can be tracked, questioned, and revised over time. This transparency builds trust and positions the presenter as a partner in evaluation rather than as an outcome promoter. Appropriately done, ROI closes conversations by enabling commitment, whether that means moving forward, adjusting course, or stopping altogether.