A short presentation is intended to force hard decisions. Time is of the essence, and you don’t have it to circle ideas, explain background information in detail, or include every insight you’d usually share in a longer talk. Let’s assume it: some meeting formats only have minutes, not hours, and that limitation can work in your favor if you plan correctly.

The objective of a short presentation isn’t just to deliver less content. It’s about selecting the right content and structuring it in a way that prompts action or understanding quickly. That means cutting anything that doesn’t directly support your message. It also means avoiding the temptation to compensate for brevity by speaking faster, showing more slides, or flooding your audience with information. None of that works. If anything, it weakens your message.

This article will offer you ten practical ways to structure and deliver short presentations that work. These are not presentation design tips. They are strategic decisions about content, pacing, and delivery.

Table of Contents

- Tip 1: Build the Talk Around One Question

- Tip 2: Skip the Setup, Open with the Point

- Tip 3: Use Time as a Structure, Not Just a Limit

- Tip 4: Treat Each Slide as a Visual Anchor

- Tip 5: Don’t Memorize, Rehearse Transitions

- Tip 6: Keep Data Tight and Interpreted

- Tip 7: End Before You’re Out of Time

- Tip 8: Limit Each Segment to One Layer of Depth

- Tip 9: Use Silence to Control Pace

- Tip 10: Write a One-Sentence Summary Before Creating Slides

- Final Words

Tip 1: Build the Talk Around One Question

Every short presentation should be built around a single, well-defined question. That question gives your talk its focus, pacing, and conclusion. It forces you to choose. It helps your audience understand what to expect, and it gives your content a natural boundary.

For example, a product update might be shaped around “What’s changed since the last release?” A sales pitch could center on “Why is this offer better than your current solution?” These are not titles; they are internal anchors. If you find yourself adding content that doesn’t directly help answer the question, cut it. In a short talk, you don’t have space for side remarks, supporting details that aren’t essential, or multiple framing angles. The point is to reduce ambiguity before you even create a slide.

Tip 2: Skip the Setup, Open with the Point

In longer presentations, it’s common to start the presentation with context, definitions, or a short anecdote before reaching the main idea. That presentation structure does not work when time is limited. In short presentations, the audience needs to know where you’re going within the first 20 seconds. You don’t have room to warm up.

The best approach is to open with your key point. Start with a sentence that reveals the core of your message. If the rest of the presentation disappeared, that sentence should still stand on its own. Everything that follows will serve either as evidence, clarification, or next steps tied to that point.

This doesn’t mean your delivery has to be cold or robotic. You can still vary your tone and use emphasis. But structurally, there’s no place for a slow introduction. Avoid beginning with “Today I’m going to talk about…” or “Let me start by giving some background.” Those phrases use time without adding meaning. Instead, go straight into the conclusion, then unpack it logically.

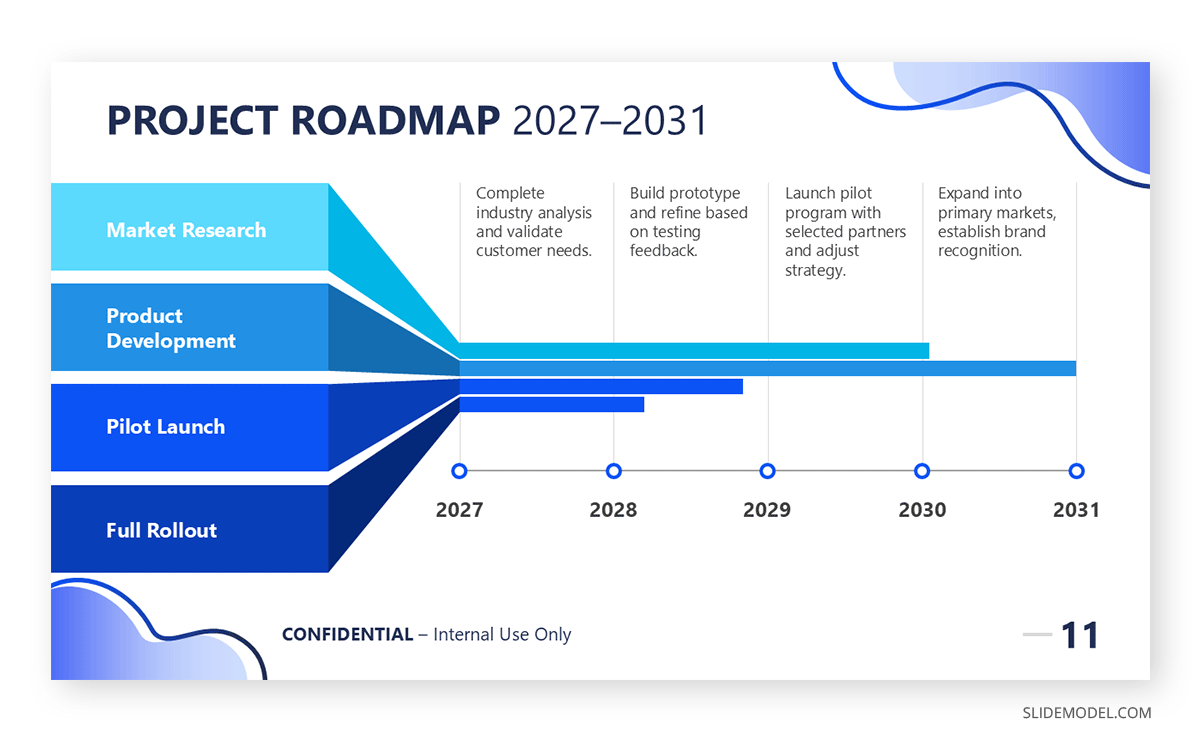

Tip 3: Use Time as a Structure, Not Just a Limit

Most people treat time limits as a constraint: something external that restricts their content. Instead, use time as your structural guide. Divide your presentation into equal parts and plan what belongs in each. Five minutes? You have time for one core point, a key example, and a brief wrap-up. Five minutes? You might fit three segments: problem, solution, outcome.

This mental shift turns time into a tool. Rather than cutting slides until you “fit,” you assign purpose to each section based on how long you’ll spend there. It becomes easier to resist tangents or unnecessary detail because each minute is already accounted for.

Let’s say you have six minutes, as in a Pecha Kucha presentation. One minute for the main message. Three for development: data, visuals, or examples. One for implications. One for closing. If you don’t plan in blocks like this, you’ll likely run out of time mid-thought or rush your ending. Both weaken the presentation.

If you aim for a specific timestamp length for your presentation, check our guide on 5 minute presentation ideas for the appropriate framework in those cases.

Tip 4: Treat Each Slide as a Visual Anchor

If your audience is reading a dense paragraph or squinting at complex charts, they’re not listening to you. That’s a guaranteed loss of attention.

Every slide should support one idea. Not two, not a summary of a section: just one. That doesn’t mean the slides have to be minimalist or empty, but they should never compete with your voice. A short presentation needs to move quickly, and that means every slide must carry its own weight. If a slide requires more than ten seconds of explanation, break it into two.

Also, avoid the trap of including all your spoken content on the slides. Short presentations aren’t meant to be standalone documents. Your slides should be visually clean and purpose-built. A number, a comparison, a visual cue; these work. A full transcript of your talk does not. You can learn more about this in our guide on how to create a slide deck.

Tip 5: Don’t Memorize, Rehearse Transitions

Short talks are often ruined by rigid delivery. When people memorize every word, they tend to either sound unnatural or lose track when something breaks the rhythm: a question, a distraction, or a technical hiccup. Instead of rehearsing lines, focus on rehearsing the structure and transitions between parts.

What matters is that you know how to move from one section to the next smoothly. These transitions are the glue that holds your message together. If you fumble them, even strong content feels disjointed. But when transitions are smooth, the audience follows your logic without effort.

Let’s say you’re moving from describing a problem to introducing a solution. A clear transition might be: “So with that challenge in mind, here’s what we built to address it.” That single line creates a natural shift. It doesn’t need to be memorized word for word, but the function of that sentence must be rehearsed. Without it, your delivery will feel abrupt or improvised.

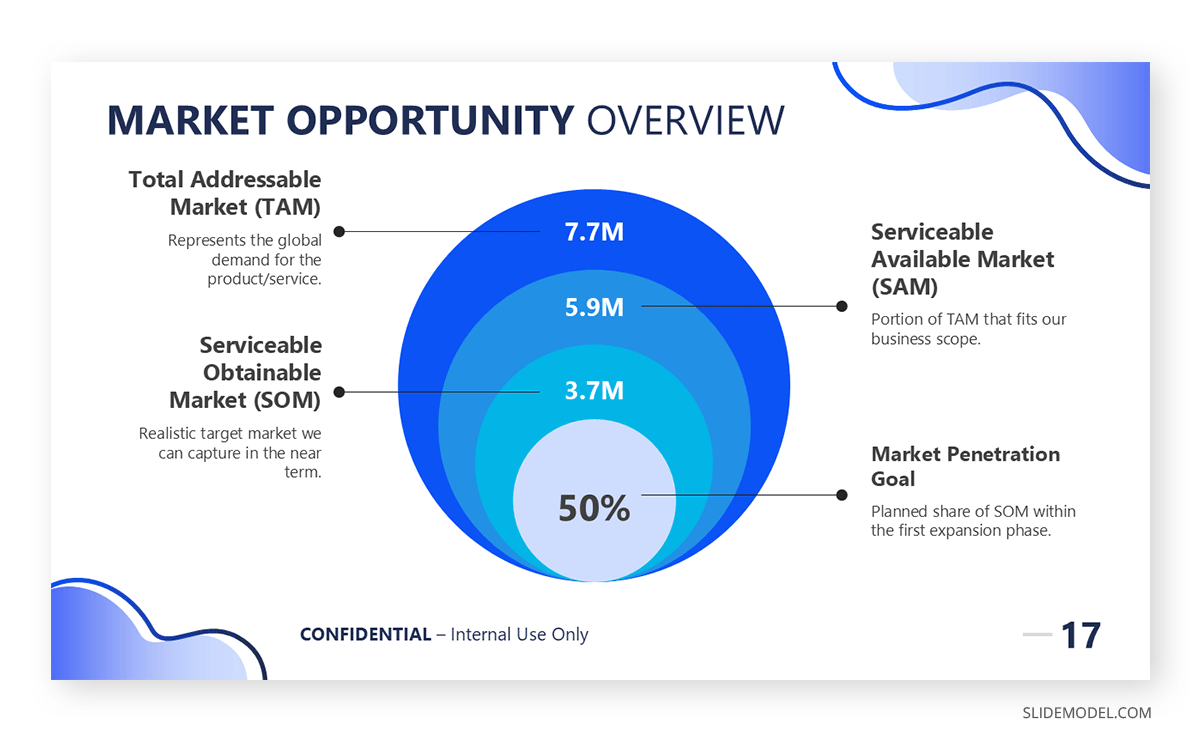

Tip 6: Keep Data Tight and Interpreted

Short presentations often include metrics, forecasts, or benchmarks; but most presenters use more data than the audience can absorb in the time available. Raw figures aren’t persuasive on their own. The point is not to show numbers, but to make them say something. In a short format, that distinction becomes critical.

One graph, one trend, or one contrast is usually enough. You don’t need multiple datasets unless they build on each other with purpose. If you’re trying to show revenue growth, don’t include five years of detailed breakdowns. Show the upward curve. Then say what caused it and why it matters now.

Equally important: interpret the data in your own words. Never assume your audience will understand the implication. If you show a number without stating what it means, you’re leaving them to do the mental work you should have done. Say, “This tells us we’ve doubled engagement in just three months,” not “As you can see, engagement has increased.”

Our detailed guide on data presentations can help you understand the requirements for these type of presentations.

Tip 7: End Before You’re Out of Time

In short talks, endings tend to get squeezed. You spend too much time explaining early points, lose track of time, and then rush the final slide or leave the talk feeling incomplete. That final impression matters more than most people realize. If the close is weak, the message gets diluted, no matter how strong the beginning was.

The solution is simple: end earlier than you think you need to. Always build in a time cushion for your conclusion. If you have seven minutes, plan to finish at minute six. If you finish early, you leave room for a closing statement or even a quick question. If you go long, you’ll still have enough time to finish properly.

But don’t just “stop talking early.” End your presentation with intention. Summarize the one key idea and point clearly to the action or insight that should follow. Don’t say “That’s it” or “Thanks for listening” as your only final remark. Those are endings by default, not by design.

Tip 8: Limit Each Segment to One Layer of Depth

You cannot go overboard in time-constricted presentations without losing time or clarity. This doesn’t imply your speech has to be shallow, it means: don’t beat around the bush. Each point should be developed to a single, self-contained layer. If further explanation is required, save it for Q&A session or a follow-up document.

Let’s say you’re presenting a new internal process. Your first layer might be: “The new process reduces handoffs between departments.” That’s your statement. One layer of depth would explain how: “We’ve removed three approval steps that caused delays.” That’s enough. Don’t go further into individual cases, policy history, or exceptions. That would take you to a second or third layer: too much for a brief talk.

Tip 9: Use Silence to Control Pace

Silence is one of the most underused tools in short presentations. Most people fear pauses because they mistake them for lost time. But in a short talk, silence is structure. It creates space around key points and helps your audience absorb what you’ve said. A power pause between segments or after an important claim signals that something matters. It slows the rhythm just enough to let the message land.

Speaking nonstop is a common mistake in fast-paced settings. Presenters feel the pressure of the clock and try to squeeze in as much as possible. The result is a blur of words with no emphasis and no retention. You may finish on time, but you’ll leave little impact.

Tip 10: Write a One-Sentence Summary Before Creating Slides

Before you create slides, draft outlines, or rehearse, write one sentence that summarizes your entire presentation. If that sentence isn’t clear, nothing that follows will be. This single sentence forces you to confront what you’re really trying to say. It becomes a compass for everything else.

For example: “This talk shows how our new onboarding system cuts training time by 40%.” That’s precise. It has a subject, a value, and a scope. A weak version might be: “We’ll explore updates to our onboarding process.” That’s vague, passive, and doesn’t justify the audience’s attention. Check our article on presentation summaries to learn more about this technique.

Final Words

Short presentations are hard because they demand trade-offs. You can’t say everything, show everything, or explain every nuance. But you don’t need to. What matters is what remains after you’ve removed the rest. The goal is not compression; it’s precision.

If you’re deliberate in how you plan, cut, and deliver, short talks can be more persuasive than longer ones. You gain the audience’s attention and keep it by respecting their time and focusing on what’s most relevant. That doesn’t mean you speak quickly or dump information. It means you structure with care, decide what not to say, and trust the simplicity of your message. You can also check our guide on how to make a presentation longer if you feel your current slide deck is missing some elements.