Business portfolio presentations occupy a particular place in corporate communication. They are neither simple performance reports nor broad strategic narratives. They require the presenter to organize a diverse set of activities, products, or business units into a coherent structure that explains how each component functions, why it exists, and how it contributes to the organization’s direction. Rather than a compendium of elements in a catalogue fashion, a business portfolio presentation is a live argument about resource distribution, business potential, and risk.

Below, we examine how presenters can build and deliver a portfolio for a company that feels deliberate, structured, and credible. We’ll list our selection of recommended business portfolio templates to speed up the presentation design process.

Table of Contents

- What a Business Portfolio Presentation Really Does

- Selecting and Categorizing Portfolio Components

- Slides to Include in a Business Portfolio Presentation Deck

- Building a Narrative in Business Portfolio Presentations

- Designing Business Portfolio Slides for Comparability

- Presenting Risk, Value, and Timing Across a Business Portfolio

- Explaining Strategic Rationale and Decision Logic

- Managing Audience Expectations and Challenging Questions

- FAQs

- Final Words

What a Business Portfolio Presentation Really Does

A business portfolio presentation has one overarching goal: to show how a collection of initiatives creates value through balance, prioritization, and strategic intention. Yet many presenters approach it as if their task were simply to list every product, project, or segment under their responsibility. This approach weakens the message from the start. Listing parts is descriptive. Portfolio reasoning is explanatory. A strong presentation emphasizes the underlying structure, the “why” of the corporate portfolio, rather than the inventory of elements.

The first duty of the presenter is to determine the purpose of the review. A company background example can be displayed to justify resource allocation, request investment, demonstrate progress, or evaluate performance across segments. Without clarity on the objective, the presentation drifts into unfocused detail. The audience needs firm orientation early: they must understand what the portfolio measures, what constraints shape it, and what decisions it supports. When this orientation is not provided, even well-prepared visuals lose impact because the audience does not know how to interpret them.

A business portfolio presentation deck also sets expectations for risk. Every portfolio contains areas of strength, areas of uncertainty, and underperforming areas. Hiding weaknesses or diluting them among positive elements creates more doubt than transparency. The presenter’s responsibility is not to protect individual components but to safeguard the system’s overall logic. A well-delivered review acknowledges vulnerabilities while explaining how the portfolio compensates for them. This demonstrates analytical maturity and enhances trust.

Recommended lecture: Risk Analysis and Risk Management in Presentations

Another fundamental function is temporal positioning. A company portfolio is never static; it represents a moment in an ongoing process. The presenter must therefore define the timeframe the audience should have in mind. Whether the review covers a quarter, a fiscal year, or a multi-year transformation influences how each component should be judged. A strong introduction clarifies the horizon: is the portfolio being assessed for stability, for growth potential, or for alignment with a new direction? This avoids unproductive interpretations and directs the audience toward the questions that matter.

Finally, a portfolio for a company highlights relationships between components. These relationships involve shared resources, complementary capabilities, interdependencies, or overlapping markets. A presenter who fails to articulate these connections presents a fragmented view that forces the audience to reconstruct the system on their own. A presenter who clarifies them creates coherence. This coherence is the difference between a series of slides and a compelling strategic review.

Selecting and Categorizing Portfolio Components

A business portfolio may contain dozens of lines of activity, but a presentation cannot. Effective presenters make deliberate decisions about what the audience must see and what can remain in supporting documentation. This selection process clarifies focus and strengthens the underlying argument.

Start by classifying components by strategic importance. Some units drive revenue or market presence; others support long-term positioning. There may also be segments that exist for defensive reasons, regulatory obligations, or legacy commitments. Mapping components by their role in the organization helps the presenter determine which pieces define the message. If a unit does not influence direction or resource distribution, it does not demand screen time in the primary narrative.

Next, categorization must serve comprehension. Clustering components into meaningful groups helps the audience interpret the system more easily. Categories may reflect product families, market segments, development stages, or performance tiers. What matters is not the category itself but the reasoning behind it. Categories imposed without explanation confuse more than they clarify. Categories designed to reflect strategic logic guide the audience toward accurate interpretation.

In business portfolio reviews that span multiple markets or industries, common denominators are essential. Presenters often struggle when components vary widely in scale or nature. Some units may represent mature operations with predictable returns, while others may be early-stage initiatives with uncertain trajectories. To avoid overwhelming the audience with incomparable elements, the presenter can use standard evaluative criteria such as contribution margin, customer reach, strategic fit, or risk level. These shared criteria allow the audience to process differences in a structured way.

Slides to Include in a Business Portfolio Presentation Deck

A business portfolio presentation should rely on a small, curated set of slide types, each serving a distinct decision purpose. Including too many formats dilutes the narrative; omitting key ones forces the audience to infer logic on their own.

The following slides form a coherent portfolio deck when used together:

- Portfolio Overview / Context Slide

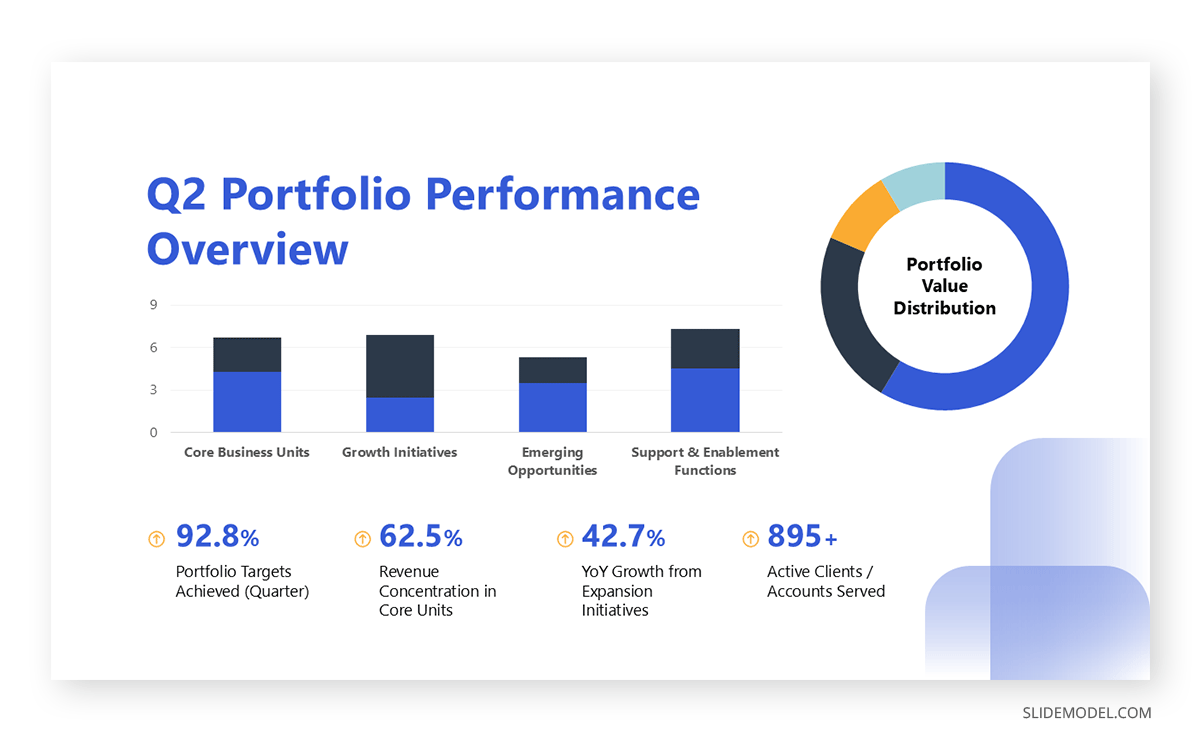

Establishes scope, timeframe, and the logic used to evaluate portfolio components. - Portfolio Performance Overview

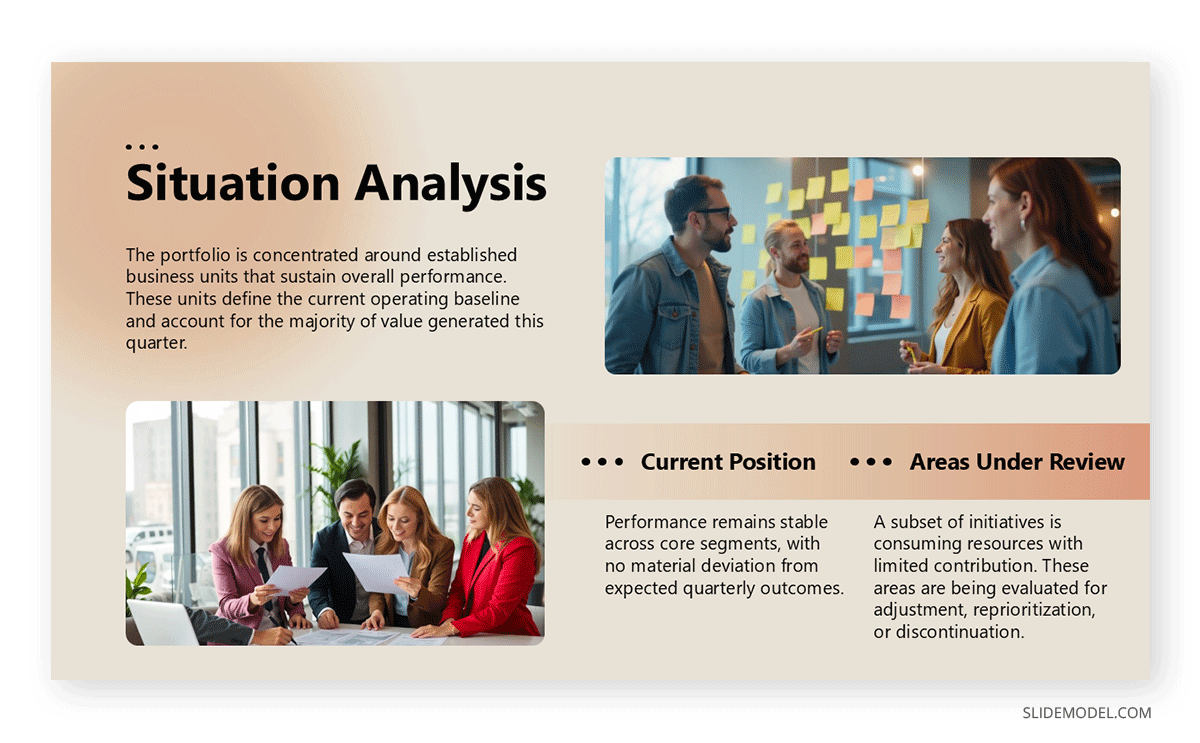

Compares core segments using consistent metrics to show contribution, trend, and scale. - Situation Analysis Slide

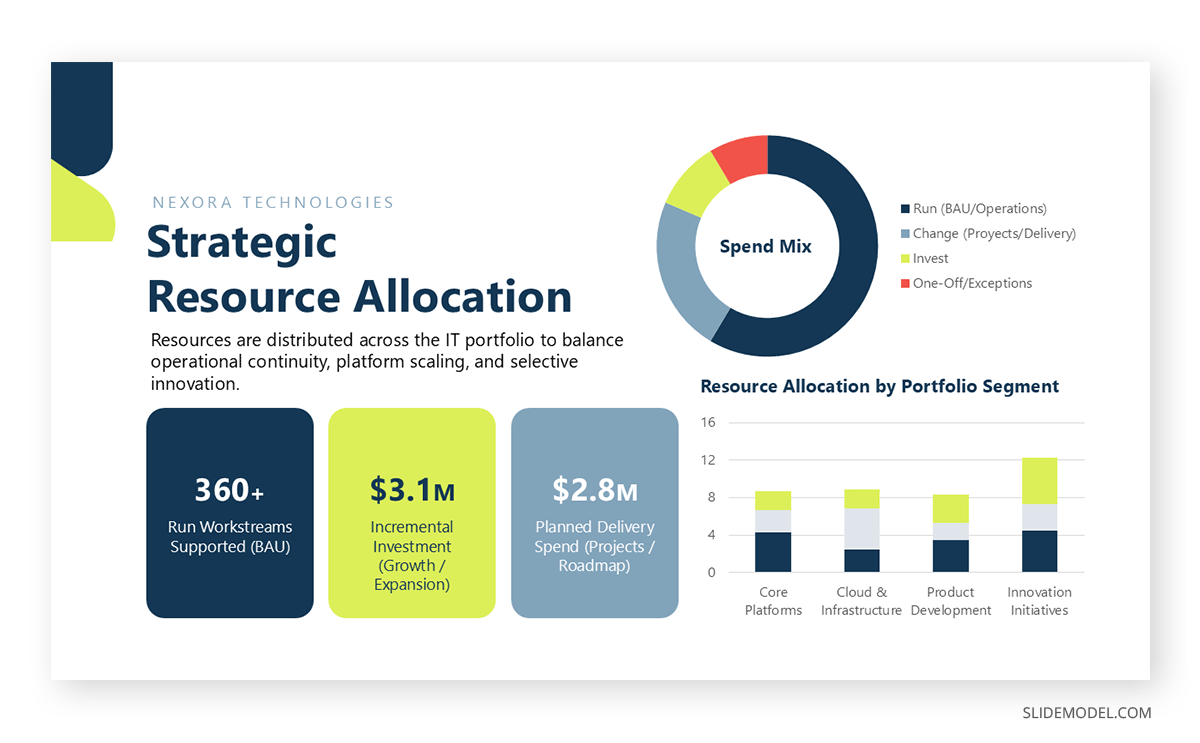

Clarifies current position, stability anchors, pressure areas, and emerging concerns. - Strategic Resource Allocation Slide

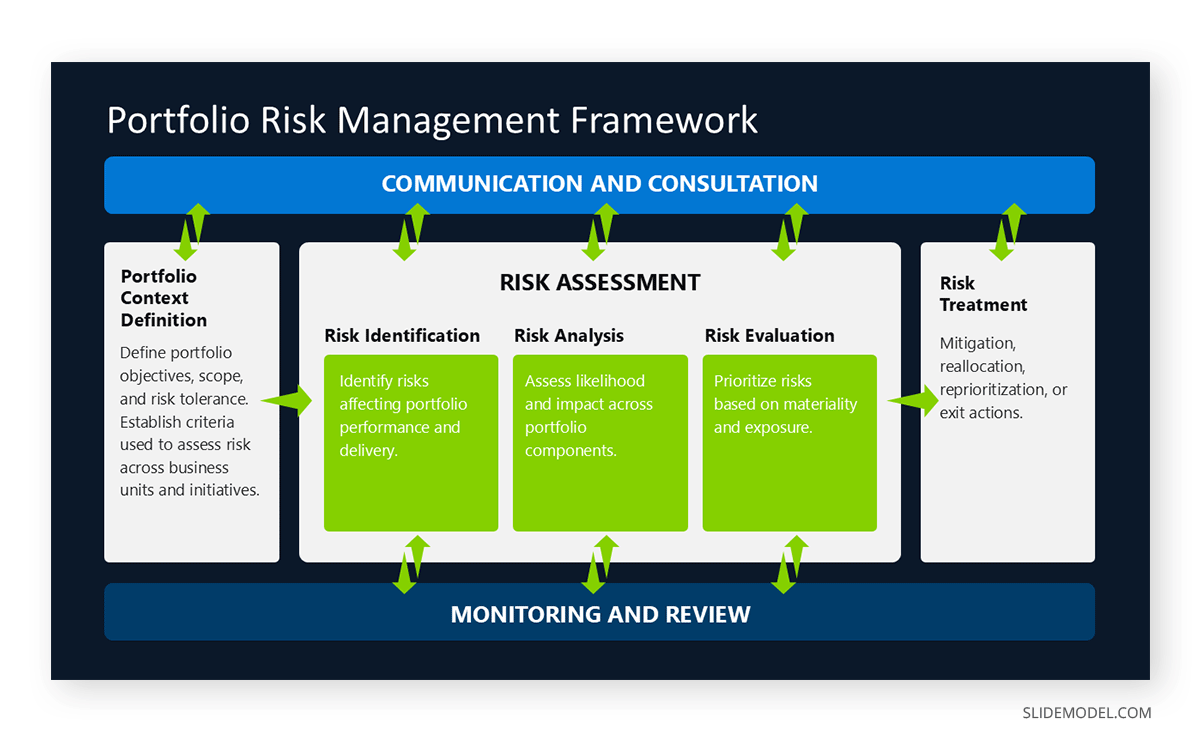

Shows how the budget, capacity, or investment is distributed across portfolio segments. - Portfolio Risk Management Slide

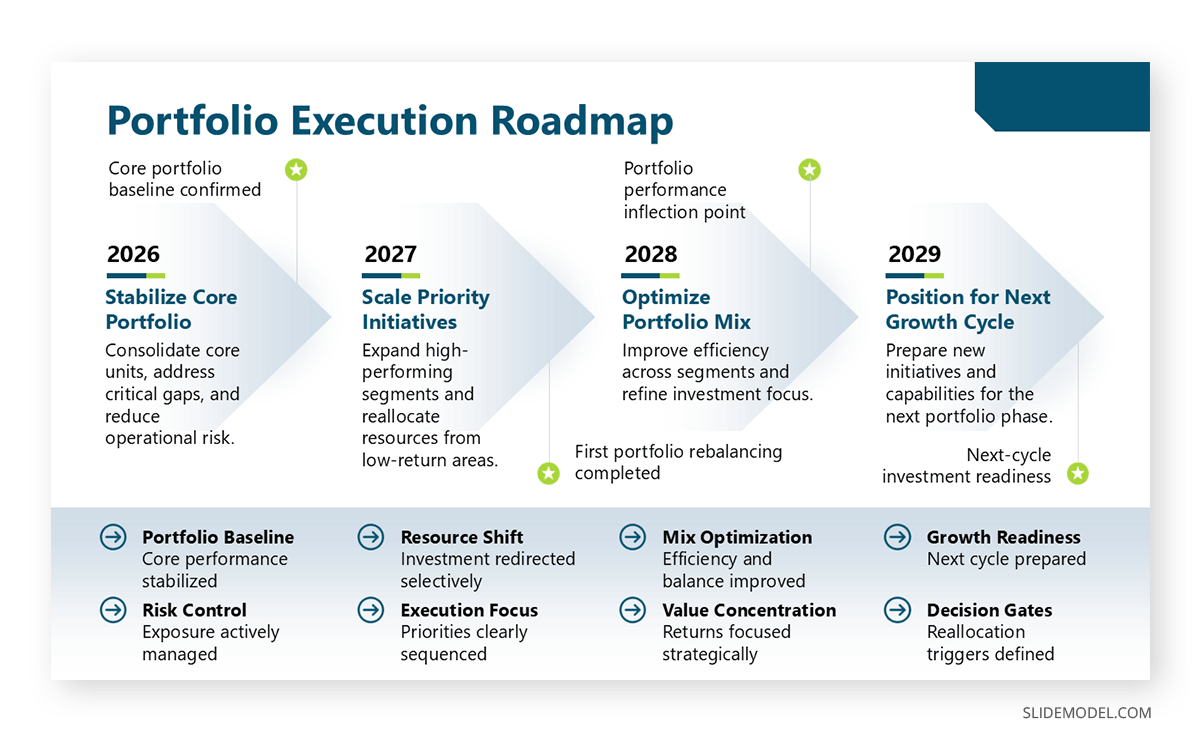

Explains how risk is identified, assessed, prioritized, and acted on at the portfolio level. - Execution Roadmap / Timeline

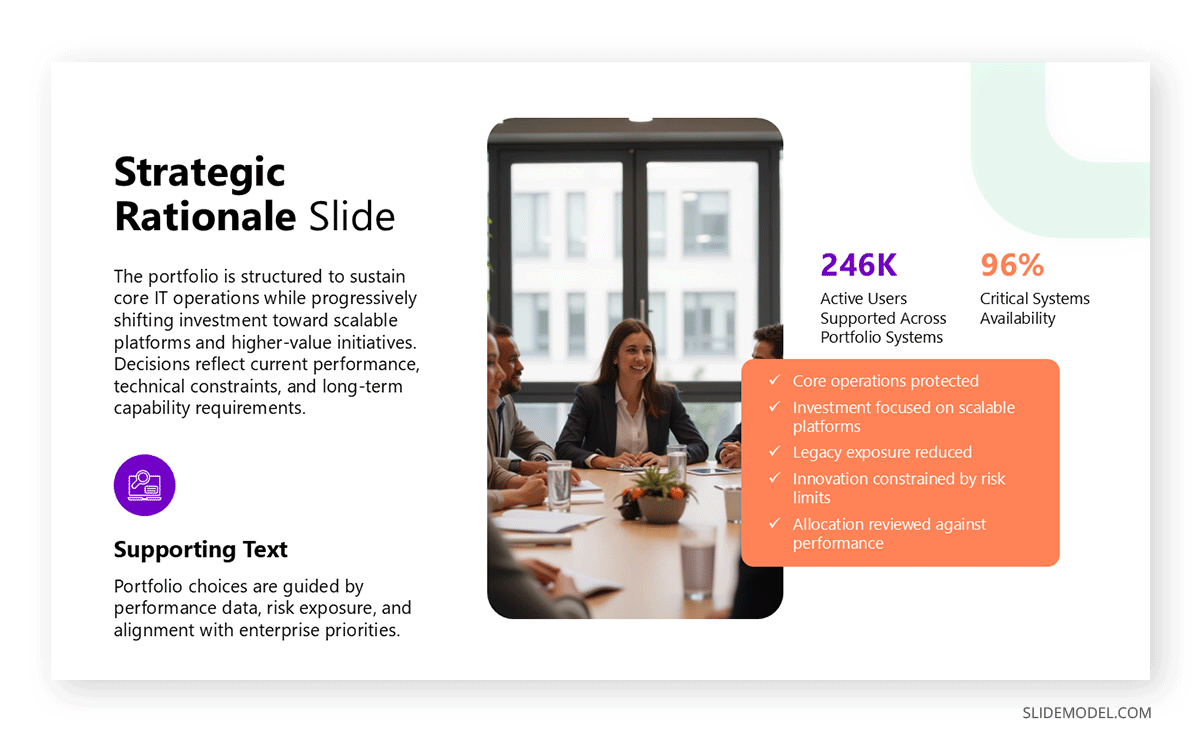

Position initiatives across time to show sequencing, maturity, and dependency. - Strategic Rationale Slide

Articulates why the portfolio is structured as it is, including constraints and trade-offs. - Decision and Next Steps Slide

Summarizes implications, reallocation triggers, and decisions required from leadership.

Together, these slides transform a collection of initiatives into a governable, interpretable portfolio system, aligned with how executives evaluate performance, risk, and direction.

Building a Narrative in Business Portfolio Presentations

Narrative in a business portfolio presentation is not about persuasion or emphasis. It is about ordering information in a way that mirrors executive reasoning. The audience expects to understand position first, then constraints, then implications.

A coherent portfolio narrative typically moves from current state, to distribution of value and resources, to risk and pressure points, and finally to forward-looking decisions. This sequence reduces the need for interpretation during the presentation and allows the audience to follow the logic without relying on verbal clarification.

Recommended lecture: Data Storytelling

Another approach is to frame the narrative around questions the audience naturally holds. For example: Where is the organization currently positioned? What supports its stability? What expands its future options? What consumes resources without adequate return? Presenting components in response to these questions shapes the audience’s reasoning and gives the portfolio coherence.

Transitions between sections are essential. Shifting from one category to another without explanation forces the audience to recalibrate repeatedly, disrupting comprehension. A clear transition may indicate why the following group matters, how it relates to the previous one, or what change in evaluative criteria the audience should adopt. These bridging explanations conserve cognitive energy and maintain narrative flow.

Designing Business Portfolio Slides for Comparability

How to present a business portfolio implies working with visual structures that allow the audience to compare multiple components quickly and accurately. While aesthetics play a role, the primary function of design is to make relationships visible. Poor design introduces distortion or confusion, which undermines the presenter’s message.

The most important principle is uniformity of structure. When each component is presented using the same visual framework: identical metrics, consistent formatting, and mirrored layout. The audience processes information more efficiently. Inconsistent designs create cognitive interference; the viewer must re-learn the slide format before interpreting the content. Uniform slides signal analytical discipline and reduce friction.

Scale is another central issue. When presenters adjust scales across components to make charts more appealing, they impair comparability. A revenue line that appears steep on one slide and flat on another may reflect only a difference in axis scaling. This misleads the audience and invites skepticism once noticed. Consistent axis values and unit representations preserve accuracy and trust.

Color use deserves careful control. Portfolio presentations often rely on color to distinguish categories or status indicators. If colors change meaning across slides, the audience loses orientation. A stable color system, one color for core units, another for growth initiatives, and a third for declining or high-risk components, allows the viewer to decode information more instinctively. Saturation should remain moderate to avoid projection issues and visual fatigue.

Information density must be managed tightly. Presenters sometimes overload each component slide with elaborate charts, large tables, and multiple indicators, thinking this signals rigor. In practice, it diminishes clarity. Components should display only essential data: scale, trend, contribution, and risk. Depth can be provided verbally or in backup slides, but the primary deck should remain accessible to the entire room, including those viewing from a distance.

Presenting Risk, Value, and Timing Across a Business Portfolio

Business portfolio reasoning revolves around three dimensions: value generated, risk carried, and timing of outcomes. A presenter who cannot contextualize these dimensions leaves the audience with an incomplete picture. Each dimension must be addressed clearly and consistently.

Value should be framed not only as revenue but as a contribution to strategy. Some units may generate moderate revenue but provide access to new markets. Others may support product ecosystems or customer retention. A presenter who explains value through multiple dimensions gives depth to the evaluation. This avoids simplistic assessments that judge components solely by current performance.

Risk requires direct articulation. Every portfolio contains exposure to market volatility, technological uncertainty, operational complexity, or competitive shifts. Presenters often hesitate to mention risk, fearing it will undermine confidence. Yet decision-makers expect transparency. The role of the presenter is to explain how risk is distributed and how the portfolio structure mitigates it. For instance, one unit may offset another’s volatility, or a phased development cycle may reduce financial exposure. When explained with clarity, risk assessment demonstrates control.

Timing is the third essential dimension. Some components provide immediate return; others require investment before producing results. Without a clear timeline slide, the audience cannot judge whether a component is performing as expected. Presenters should therefore specify the stage of each initiative: mature, expansion, pilot, or exploratory. They should also indicate whether current performance aligns with stage-specific expectations. This positions the audience to evaluate not only results but also their relevance.

Explaining Strategic Rationale and Decision Logic

Strategic rationale in a portfolio presentation answers a narrow but critical question: why this structure, now. It is not a vision statement and not a retrospective justification of past decisions.

Effective rationale connects portfolio structure to constraints that cannot be ignored, such as capacity limits, technical debt, regulatory exposure, or execution risk. It explains not only where investment is directed, but also where it is intentionally withheld. This distinction is often missing in weaker portfolio decks.

Presenters should begin by identifying the criteria used to evaluate components. These criteria include profitability, customer impact, regulatory relevance, or alignment with long-term business goals. Presenting the criteria early enables the audience to follow the rationale even before the components appear. They understand what matters and how judgments are formed.

The rationale must also connect to constraints. No organization operates with unlimited resources. Constraints may involve budget ceilings, talent shortages, technology readiness, or competitive pressures. When a presenter clarifies constraints, the distribution of resources appears deliberate rather than arbitrary. This prepares the audience to understand why some units are prioritized over others.

Another part of the rationale involves legacy decisions. Portfolios often contain components created in response to past needs. The presenter must distinguish between what remains relevant and what persists only because it has not yet been retired. This distinction shows analytical honesty and sets expectations for future adjustments. Leaving legacy components unaddressed suggests avoidance rather than strategic intention.

The presenter should also show how learning influences decisions. A portfolio evolves as feedback accumulates from markets, operations, and customers. Explaining how lessons have shaped recent adjustments demonstrates adaptability. It positions the portfolio as a living system responsive to evidence rather than a static structure.

Finally, the rationale strengthens when it anticipates objections. Decision-makers will question why specific initiatives continue despite underperformance or why new ones deserve investment. A strong presenter addresses these concerns proactively, showing how each element fits within the desired trajectory. This anticipatory explanation reduces friction and builds confidence in the presenter’s analytical maturity.

Managing Audience Expectations and Challenging Questions

Business portfolio presentations are often delivered to senior leaders or investment committees. These audiences evaluate both the content and the presenter’s strategic thinking. Preparing for their questions is as important as preparing the slides themselves.

Senior audiences focus on impact, risk exposure, and return on resources. Their questions aim to test whether the presenter understands not only individual components but the system as a whole. Anticipating these questions requires identifying areas of potential concern: units with declining trends, initiatives requiring investment, or segments that appear misaligned with strategy. Preparing clear, concise responses strengthens credibility.

Another expectation is decisiveness. Senior audiences look for presenters who can articulate priorities without hesitation. Presenters should therefore be ready to explain which components they would expand, maintain, or phase out if resources change. This demonstrates strategic clarity.

Handling difficult questions requires composure. A defensive tone suggests insecurity; an overly casual tone signals a lack of seriousness. The appropriate approach is factual and grounded: acknowledge the question’s validity, provide context, and connect the answer to the business portfolio structure. This method maintains authority while engaging respectfully.

FAQs

What is the main objective of a business portfolio presentation?

Its objective is to show how multiple business units, products, or initiatives function as a system. The presenter must demonstrate how each component contributes to the organization’s direction, how resources are distributed, and what trade-offs or risks shape decisions.

How much detail should each component include?

Only information that helps the audience understand its scale, trend, potential, and risk. Additional data belongs in appendices or supporting material. A component slide should never feel like a full report; it should enable interpretation, not overwhelm.

How do I decide which components to highlight first?

Begin with the units that define the organization’s current position or revenue base. Then move to growth initiatives and emerging opportunities. This sequencing mirrors how decision-makers evaluate the system, helping the audience understand context before nuance.

How do I present underperforming units without weakening the message?

Address them directly. Explain the performance criteria, the source of the weakness, and planned actions. Transparent discussion shows control. Avoid downplaying the issue, but avoid dramatizing it too; neutrality fosters trust.

What visual format works best for showing multiple components in business portfolio slides?

Use a uniform template for all units: identical layout, consistent metrics, and aligned charts. Uniformity allows immediate comparison. Avoid mixing design styles or altering scales, as this introduces distortion and disrupts pattern recognition.

How should timelines be integrated into the business portfolio presentation?

Each component should have an implied or explicit timeframe: mature, expansion, pilot, or exploratory. Without this, the audience cannot judge whether the performance aligns with expectations. Timeframes also help explain investment needs and future potential.

What role does storytelling play in a corporate portfolio presentation?

Storytelling provides structure. It organizes components into a logical sequence that matches how reasoning unfolds. It is not used for embellishment but for orientation, helping the audience move from the current state to the future direction with clear transitions.

Should I show projections or only current data?

Show projections only when their assumptions are explicit and tied to observable trends or strategic initiatives. Unsupported projections create doubt. When used appropriately, projections help position the portfolio across time.

How should I prepare for senior-level questions?

Identify potential concerns in advance: underperformance, investment levels, alignment issues, and risk concentration. Prepare short, factual explanations and be ready to connect each answer back to the portfolio structure. Senior audiences look for coherence, not memorized scripts.

Final Words

A business portfolio presentation is a test of structure, clarity, and analytical maturity. The presenter’s task is not to memorize data but to articulate relationships, decisions, and direction. A well-delivered portfolio review reveals how the organization allocates attention and resources, balances present needs with future growth, and responds to evolving conditions.

The strength of a portfolio presentation lies in the discipline behind it: selecting what matters, categorizing with intention, designing for comparability, explaining rationale, and addressing uncertainty with composure. When done well, the presentation becomes more than a report. It becomes a demonstration of strategic thinking.