Every day we make a myriad of decisions – eat out or buy groceries, walk or hail a cab, go to the movies or stay in. Sometimes, we rationalize that cooking a home meal is a better idea since we already spent too much on dining this month. But then, we see some attractive promo at the deli and go on and change our mind in a beat. In a nutshell, behavioral economics attempts to study how our “whims” affect our day-to-day spending decisions and affect different economic processes on a macro level. Let’s dig in!

Behavioral Economics Definition

Formalized and developed by a recent Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler, the theory of behavioral economics investigates how different psychological, social, and cultural factors impact our decisions and reflect in respective economic outcomes.

Some of the key question this theory looks into are as follows:

- What are the psychological motivations that might prompt someone to choose a specific investment option over another?

- Why do people frequently fail to make what would seem to be rational decisions when viewed by outside observers?

- How does a person’s cultural or social background influence their day-to-day decisions?

How Behavioral Theory Differs from Traditional Economics

Traditional economic theory is built atop the so-called “homo economicus” model – a theory that people will always operate in their own best interests and rely on rational judgments for any decisions.

Behavioral economists argue that it’s not always the case. Factors such as emotion or bias are deeply engrossed into unpredictable human nature. And they manifest themselves in our decision-making.

Thus, behavioral economists try to zoom in on the psychology driving our decision making, especially when those decisions conflict with the standards of rational economic theory.

The Main Theories and Principles of Behavioral Economics

While every economic decision is different, there are several behavioral economic principles that universally apply. Below is a quick overview of these.

Nudge Theory

Richard Thaler is the father of the Nudge theory, one that won him a Nobel prize in 2017. The central concept – nudge – is a policy-making technique that relies on indirect suggestions, positive reinforcement, and other tools to foster the right course of action.

Instead of forcing people into a certain choice or penalizing them for not doing something, nudge theory suggests that we should make a certain choice easier.

For instance, instead of punishing people with late fees, an organization can create an automatic payment process for debiting everyone’s accounts on a certain date.

Some of the key postulates of this theory are as follows:

- Leaders and authorities will have more success if they design choices while considering how people actually think and make decisions. This means realizing that decisions are generally made instinctively and irrational, rather than assume that all people make decisions and think (logically and rationally).

- Nudge theory works by using choice architecture. Its goal is to propose a set of options in a way that makes it likely for someone to pick a predetermined, more desirable option.

- Also, this theory favors indirect encouragement and enablement over direct instructions. For instance, instead of saying that everyone is prohibited from bringing their own devices to work, you may want to upgrade the team’s workstations so that fewer are encouraged to do so.

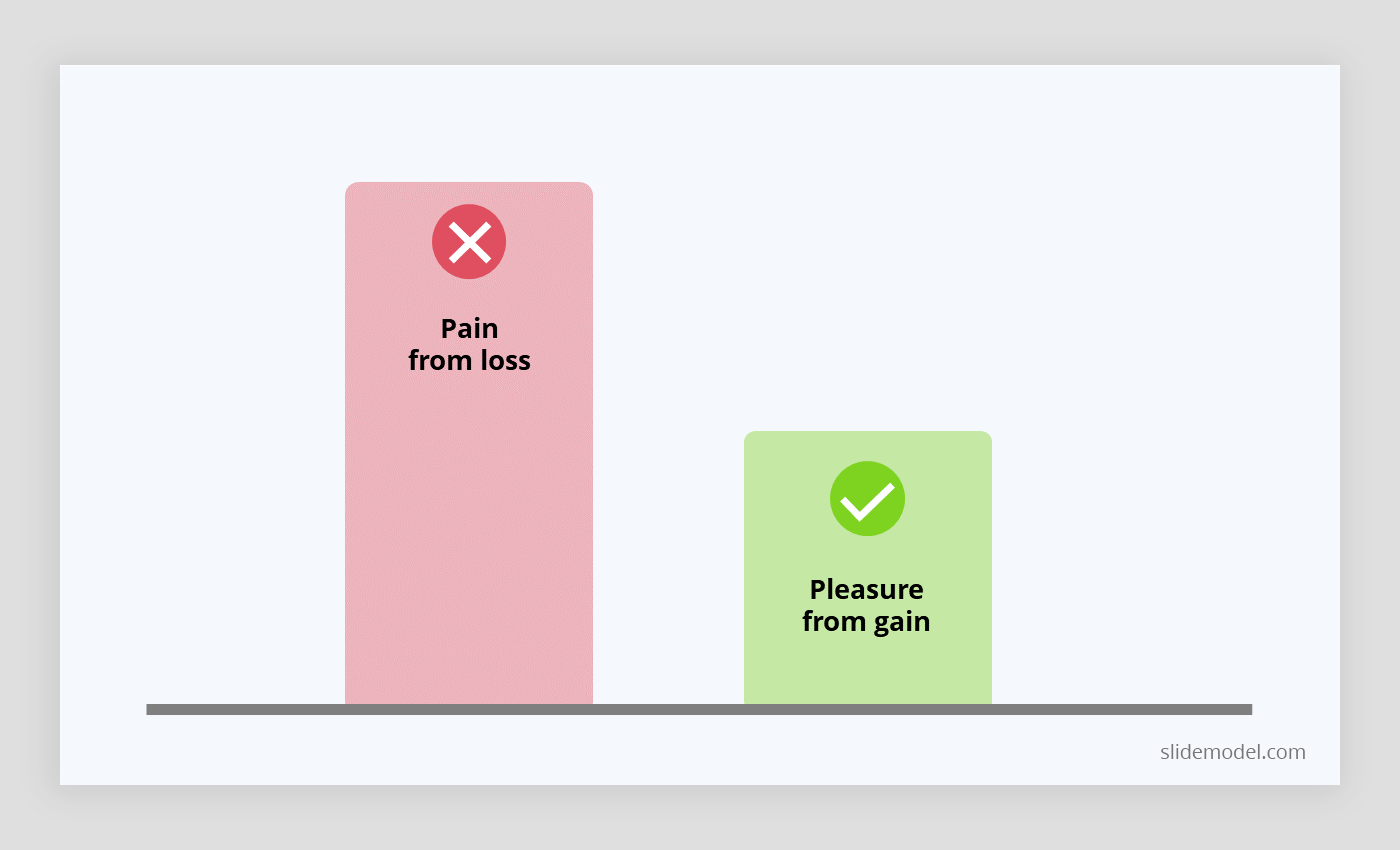

Loss Aversion and Prospect Theory

Prospect theory (or loss-aversion theory) analyzes why we value losses and gains differently and how this tendency impacts our decisions.

This theory found that when presented with two equal choices, most of us will choose one that has a higher perceived value (gain $25) over the other that assumes some loss (gain $50 but lose $25).

Learn more about loss aversion and prospect theory from our previous post.

Sunk Cost Fallacy Theory

When thinking rationally, most educated people understand that some costs can never be recovered. For example, you can’t do much about a non-refundable ticket to a concert. However, we have a tendency to still cling onto the time or money we once invested in something. This is the basis of sunk cost fallacy bias.

Availability Heuristics

Sometimes our brain uses a mental “shortcut” and brings up some information we remember best to explain what’s likely to happen. For instance, news about a recent airplane crash can make someone more fearful of flying. Though, officially airplanes are the safest travel option.

This tendency is called availability heuristics.

And oftentimes we make decisions based on the surface information alone, instead of digging deeper into the matter.

Endowment Effect

Endowment Effect refers to the people’s tendency to overvalue objects they already own, and their unwillingness to sell those items for their actual price. When people feel sentimental about something, this effect can be very strong. For instance, you may hold on to an inherited property you grew up in instead of selling it when the real estate market is hot.

Bounded Rationality

This theory indicates that our ability to make good decisions is strongly limited (bounded) by several factors:

- The information we have a hand

- Our cognitive abilities and critical thinking skills

- The finite amount of time we have to make that decision.

As a result, most of us act as “satisfiers” – decision-makers who settle for a satisfactory solution, rather than the best one.

Reciprocity

Reciprocity principle emphasizes that we often treat others based on how we got treated. If some did us a favor, we are very likely to return it in some way. The reciprocity principle is often used as a marketing tactic for lead generation. For instance, a retailer may pitch you a 10% discount for subscribing to their newsletter (and giving away your email address). Or include some free samples to your order in hope that you’ll purchase from them again.

Status Quo Bias

Inherently, most of us want things to stay the same. Thus, we often prefer to stick with the familiar rather than trying new “unknown” stuff. This tendency is called status quos bias. A Harvard study provides the following example of this bias in action:

A couple of years ago, authorities in Germany decided to relocate a small town close to a strip-mining project to another location – a similar valley nearby. Urban planners suggested a variety of new town planning options, but the local folks selected a plan extraordinarily like the serpentine layout of the old town – one that was neither particularly good or convenient, albeit very familiar.

6 Must-Read Behavioral Economic Books

Care to learn more about the key concepts and theories, central to behavioral economics? Here are six books we recommend along with a very brief synopsis of each.

1. Daniel Kahneman – Thinking, Fast and Slow

Daniel Kahneman, another Economics Nobel Prize winner, is another “founding father” of the behavioral economics movement. Think, Fast and Slow book delivers some of his grounding ideas in an accessible manner. It explains that most of us have two systems inside our brain:

- System 1 (Fast): an automatic and impulsive one that prompts us to make instinctive decisions (both rational and irrational ones). It’s a bit of a remnant from our past.

- System 2 (Slow): highly conscious, aware and considerate. This system is a fresher addition to our brain and its main responsibility is to exert self-control and deliberately focus your attention.

The book further discusses how these two systems control and influence our behaviors every day, explains the different bias and heuristics that we experience due to this constant battle and what you can do about that.

“A general “law of least effort” applies to cognitive as well as physical exertion. The law asserts that if there are several ways of achieving the same goal, people will eventually gravitate to the least demanding course of action. In the economy of action, effort is a cost, and the acquisition of skill is driven by the balance of benefits and costs. Laziness is built deep into our nature.”

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow

2. Richard Thaler – Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics

Misbehaving is the central read on the subject. Written in an engaging and conversational matter, the book explains in plain terms how human nature challenges the maths of traditional economic theory. Using real-life examples from the NFL Draft and TV game shows, Thaler demonstrates how we fail to make rational decisions and highlights the core reasons for that.

“For four decades, since my time as a graduate student, I have been preoccupied with these kinds of stories about the myriad ways in which people depart from the fictional creatures that populate economic models. It has never been my point to say that there is something wrong with people; we are all just human beings—homo sapiens. Rather, the problem is with the model being used by economists, a model that replaces homo sapiens with a fictional creature called homo economicus, which I like to call an Econ for short. Compared to this fictional world of Econs, Humans do a lot of misbehaving, and that means that economic models make a lot of bad predictions, predictions that can have much more serious consequences than upsetting a group of students. Virtually no economists saw the financial crisis of 2007–08 coming,* and worse, many thought that both the crash and its aftermath were things that simply could not happen.”

Richard Thaler, Misbehaving

P.S. As a preview, you can also watch Thalers one hour talk at Google.

3. Michelle Baddeley – Behavioral Economics: A Very Short Introduction

Baddeley’s book offers a quick dive into the field of behavioral economics, making a solid first read into the matter. Specifically, Baddeley talks about:

- Why we make decisions that are irrational

- How we are influenced by emotions, personality, and social triggers.

- Why riskier situations tend to lead to more mistakes.

“Behavioural economists have a complex range of views about what it means to be rational. Mostly, they allow that our rationality is variable and dependent on the circumstances in which we find ourselves”

Michelle Baddeley, Behavioural Economics

4. Dan Ariely – Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions

While not specifically about economics, this book lays out much of the foundation that influences behavioral economics. It turns the idea that decision-making is rational for most of us upside down by exposing us to a variety of emotional and environmental factors that impact those choices.

For example, someone may spend a significant amount of money on a meal, but also cut coupons to save a much smaller amount of money. Another is coffee. Not long ago, most people wouldn’t have considered more than a dollar or two. Now they spend over 5 dollars easily. Bet you can recognize some of the mentioned patterns in yourself!

“We usually think of ourselves as sitting the driver’s seat, with ultimate control over the decisions we made and the direction our life takes; but, alas, this perception has more to do with our desires-with how we want to view ourselves-than with reality”

Dan Ariely, Predictably Irrational

5. Richard Thaler & Cass Sunstein – Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness

Another classic book from Thaler that explains the aforementioned nudge theory and showcases how it can be applied in real-world settings. Also, it provides a great level of insights about the most common bias in our judgment such as anchoring, availability heuristic, herd mentality, status quo bias, and several others. It’s a fine, fundamental read, albeit written in an easy-to-grasp manner.

“A nudge, as we will use the term, is an aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives.”

Richard Thaler, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness

6. Gneezy, Uri & John List – The Why Axis: Hidden Motives and The Undiscovered Economics of Everyday Life.

Gneezy and List use behavioral economics as a tool to understand what motivates and incentivizes us in our everyday lives. Interestingly enough, the book even demonstrates that money is often not the greatest drive for our actions. Further, they dive into more complex subjects like discrimination and the underpinning social and psychological factors behind it.

In short, this book attempts to answer a simple question: ‘Can economics be passionate?’ The answer is clearly, yes!

“Most of us don’t respond well to delayed gratification; we are much more interested in immediate rewards. This is why we procrastinate, fail to save as much money as we should for retirement, eat too much, and exercise too little.”

Uri Gneezy, The Why Axis

To Conclude

The better we understand behavioral economics, the better we understand how we, our customers and our employees make decisions. Likewise, we can learn to design choices and incentives for others in order to get the results that we want! Also, check our complete collection of Eisenhower Matrix PPT.